After hearing some ominous thuds, our protagonist exits the locker room, her naked body still dewy from the shower. A car, the same flame-adorned Cadillac she was dancing on just a few hours ago (she’s an exotic dancer), waits for her outside. She responds to its seductive call by entering the vehicle, and a few tense moments later, the car bounces in sexual glee. We finally get a glimpse inside the car to see our hero tied up in the bondage-esque seatbelts as she, simply put, has sex with the car.

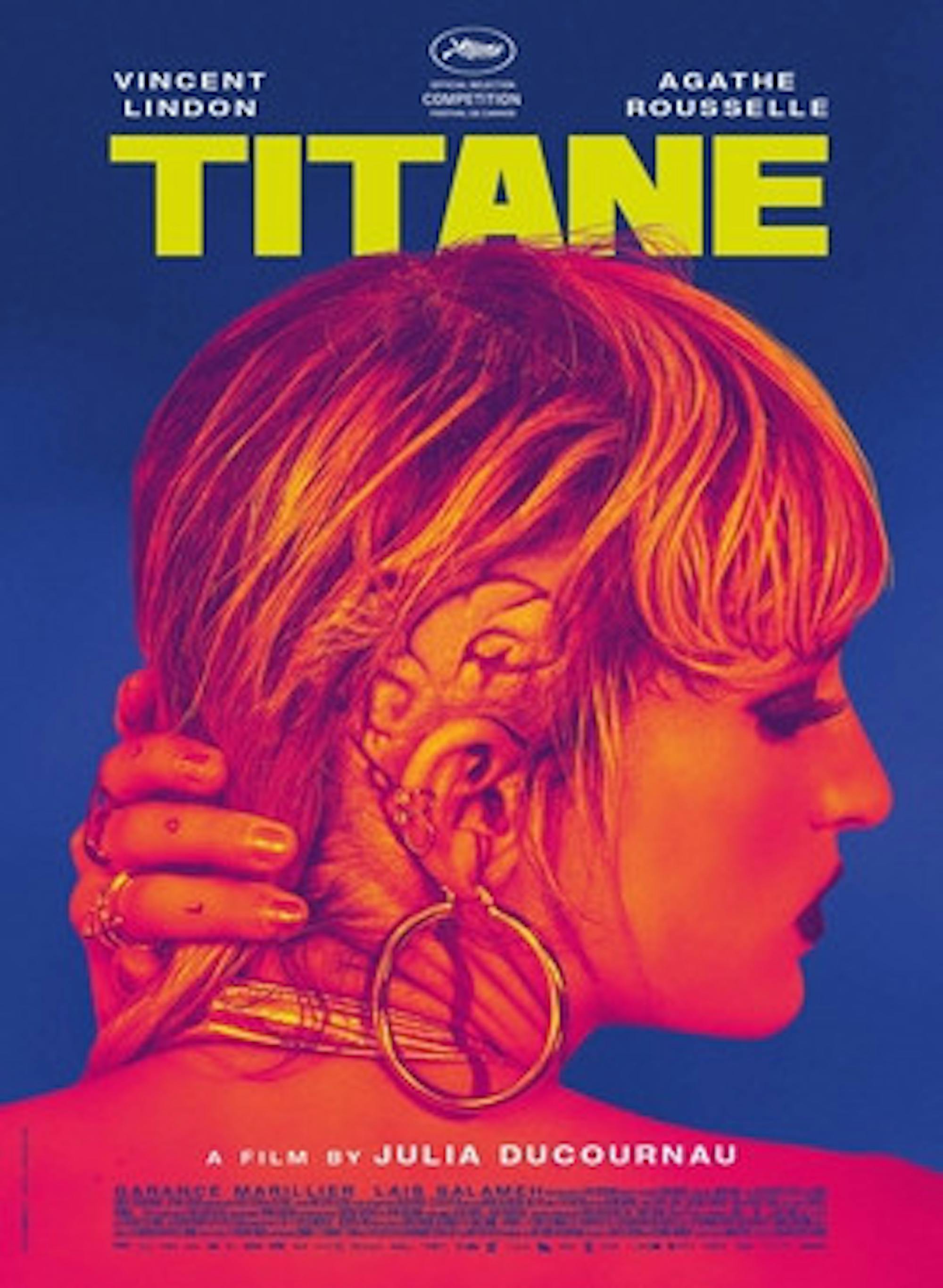

This is one of many provocative scenes of Julia Ducournau’s “Titane,” which hit American theaters on Oct. 1. It premiered globally at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where it joined the ranks of “Taxi Driver” (1976), “Apocalypse Now” (1979), “Pulp Fiction” (1994) and “Parasite” (2019) as the winner of the fest’s top prize, the Palme d’Or. Since the festival in July, the film has generated enough buzz to earn it the most successful U.S. opening weekend for a Palme d’Or winner in 17 years, since “Fahrenheit 9/11” (2004). This achievement is perhaps even more impressive considering Americans’ historical distaste for foreign language films (“Titane” is in French).

The aforementioned protagonist is Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), a serial killer with a titanium plate in her head after a car crash in her youth. After the sexual encounter with the car, Alexia is troubled to discover that she’s pregnant. On top of that major stressor, local media seems to be mounting interest in the suspicious killings going on in southern France. To flee from the police, Alexia disguises herself as a boy, Adrien, that’s been missing for 10 years, and moves into the firehouse in which his grief-stricken, steroid-abusing father lives.

Primarily, the film is concerned with the body — our carnal instincts, the fragility and decay of the human form and how we manage it. It begins with sex, removing any higher feelings or emotions from basic pleasures by comparing us to machines (like the sexy Cadillac that is the object of Alexia’s sexual desires). From this comes pregnancy, which the film uses as a vehicle (no pun intended) to introduce the necessary emotional connection we have with our bodies. We then explore the toll that connection has on our protagonist through the visual disfigurement of her body and graphic depiction of how she treats it. These scenes are interwoven with those about her growing relationship with Vincent (Vincent Lindon), the father of the boy she’s pretending to be. As he provides her with unconditional love, she must learn to reciprocate that. The film’s exploration of flesh reveals the constant negotiation between mind and body.

The movie has no shortage of jarring moments, and some critics, like A.O. Scott of The New York Times and Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post have argued that it’s so consumed by its shock factor that it doesn’t fully come together. This criticism, though, seems to misunderstand that for “Titane,” surrealist body horror is at the core of its moving thematic work. The film’s greatest strength is how well it combines what we see with how we feel — it manages to tell a story of unconditional love through its uncomfortably graphic examination of how we control our little sacks of flesh we call bodies. Ducournau’s ability to combine plot and visuals to comment on a theme is truly breathtaking here, and her evenly distributed commitment to these elements is what makes the film so cinematic. Each shot is meticulously directed, as if she’s pointing at the screen, screaming at what you should be focusing on and holding your head there so you don’t look away when, for example, Alexia tugs at her coworker’s nipple piercing with a vigor that threatens to tear it out.

Ducournau’s directorial prowess is met with equally committed acting from her stars. Lindon, a well-established French star, artfully balances his character’s desperation for both his fleeting masculinity as well as meaningful human connection. His performance is necessarily spectacular, but newcomer Rousselle’s performance truly steals the show. Her role contains surprisingly few lines, so simple body language and expressions matter, and her experience as a model perhaps helped her there. In addition, she’s tasked with playing both Alexia, the serial killer protagonist, and Adrien, the missing boy she’s disguised as. Ducournau’s tenacious insistence on showing graphic bodily distortion relies a fair bit on unforgiving closeups, and demands Rousselle to be near perfect. She delivers absolute excellence throughout.

Just Tuesday, “Titane” was selected as the French submission to the Academy Awards for consideration in the best international feature category. It will likely be nominated because of its box office success, critical acclaim and overall buzz factor, but it’s perhaps a bit too provocative for the historically more conservative-leaning Academy — remember how surprising it was when “Parasite” won best picture? Though it certainly deserves nominations across the board, especially for directing and even makeup, its chances seem low given that it is both non-English and a bit polarizing.

If you’ve noticed an overabundance of adjectives here, it’s because this is a film that requires them: “Explosive” and “monumental” are two more I’ll add to the list. I left the theater consumed by a sense of awe I’ve never felt after watching a movie, and couldn’t shake the feeling that this is exactly what cinema should do. Each scene left me completely floored, and at times the audience at the theater burst into laughter at its over-the-top absurdity (the film is incredibly self-aware). Most movies are passive viewing experiences. “Titane” is not.

Despite its magnificence, it’s hard to recommend. “Titane” is unlike any movie you’ve ever seen, and if you found the birth of Renesmee Cullen in “The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn - Part 1” (2011) unsettling, then this is certainly not for you. It’s not hard to see how people may despise this movie, but I’d encourage viewers to open their minds a bit. It’s well worth the squirms.