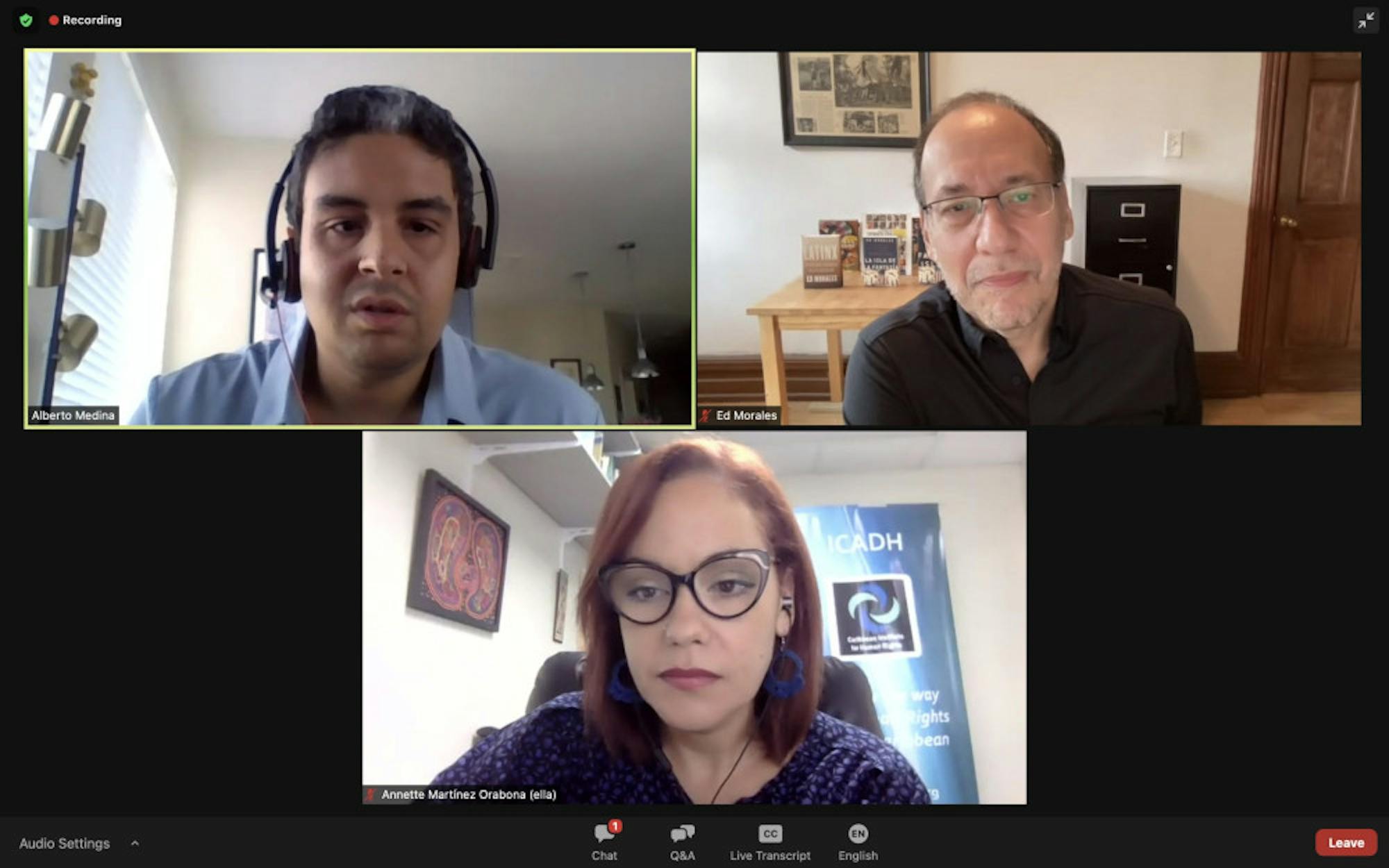

The Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life virtually hosted its first-ever speaker series event conducted entirely in Spanish on Oct. 13 during Hispanic Heritage Month. The event, titled "The Oldest Colony in the World: Perspectives on Puerto Rico's Political Future," featured international human rights lawyer Annette Martínez-Orabona (F’08) and Ed Morales, journalist and lecturer at Columbia University. The discussion offered live translation in English.

Alberto Medina, communications team lead for Tisch College’s Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), who moderated the event, explained the importance of discussing Puerto Rico in the language most accessible to those on the island.

“I think there was a trade-off that we were making," he said. "I think I expressed in the intro to the event why I thought it was important to do it in Spanish for the purposes of equity and inclusion of the community that we were speaking about.”

Medina added that Tisch decided on live interpretation for the event to allow non-Spanish speakers to more meaningfully follow along with the discussion.

“Our original plan was to do live captions," Medina said. "Instead, we thought it would be more engaging for people to be able to listen to someone's voice, and then have the simultaneous interpretation, instead of just having to kind of read the whole event [in English for] people who didn't speak Spanish.”

The guest speakers engaged with a variety of political issues facing Puerto Ricans today, ranging from the historical context of the current territorial government to climate change and economic crisis.

Puerto Rico, which has been a U.S. territory since 1898, has faced continued questions over its future, including whether it should pursue U.S. statehood or independence. Many on the island, according to Medina, do not feel the status quo is acceptable.

Martínez-Orabona told the Daily that additional tension has been building in Puerto Rico since Hurricane Maria struck the territory in 2017.

“There have been points of inflection that have brought forward a sentiment, a collective sentiment, that something needs to change," she said. "Certainly after Hurricane Maria things have become untenable for us in our daily living. It is just difficult. It was difficult before but it's getting worse and worse.”

Valerie Infante, founder and president of the Puerto Rican Association, echoed Martínez-Orabona's thoughts about the impact of Hurricane Maria, given Puerto Rico’s current unincorporated territorial status.

“The effects of Hurricane Maria really exacerbated the colonial status of Puerto Rico because of the lack of help from the US," Infante, a junior, said. "That viewpoint is often silenced, whether through political parties, or older people or the United States themselves.”

Martínez-Orabonasaid that there is currently a human rights crisis in Puerto Rico, with little help coming from the U.S. government.

“People don't know if they will be able to pay for their retirement, or their basic services like for housing or for energy or power or water," she said. "Puerto Rico is one of the jurisdictions in the United States with the highest prices for electricity bills."

Infante said that the perspectives that Martínez-Orabona and Morales brought to the conversation contrasted the narratives most commonly heard about Puerto Rico.

“I do think it was a very critical lens of the United States that I think needed to be said in a university like this one, a predominantly white institution that has a large international relations program," she said. "I think that was making a statement.”

At the core of these issues is the complicated relationship Puerto Rico has with the United States. The event's speakers cited the territory's lack of self-determination and the U.S. government's lack of commitment as hindering Puerto Rico's ability to build a successful future. Martínez-Orabonaidentified Puerto Rico’s legal status as a contradiction to the values of self-governance at the core of the U.S. Constitution.

“We don't even have, in my opinion, a valid, self-elected government in Puerto Rico," she said. "What we have is a board, comprised of seven people that are appointed by the president of the United States ... and they make these decisions for us in our name.”

Despite these sentiments, Martínez-Orabonasaid that some Puerto Ricans were still wary of a future divorced from the United States.

“You know you hear it from your parents, from your grandparents and ... there are even phrases that have been popularized with this like, ‘Que nos haríamos sin ella' — 'What will we do without that flag' — referring to the United States,” she said.

Medina sees a successful future for Puerto Rico if the international community comes together to promote the island's best interests.

“I think we need a little bit of everything," he said. "Puerto Rico goes to the United Nations every year and advocates for its case to be seen, not just by the Committee on Decolonization ... but by the General Assembly. Because the truth is that the U.S. went to the General Assembly in 1952 and got Puerto Rico removed from its list of non-self-governing territories. So, the international community had a role at that point. Perhaps it should have a role now.”

The best solution for Puerto Rico, according to Martínez-Orabona, is one in which Puerto Rico has enough stability to make a decision on its future that is independent from the pressures placed upon it by the century of occupation.

“The occupier state is supposed to provide, facilitate and engage with the territory, to make sure that that territory has sustainable ways of leaving and providing for itself," she said. "And once you have that then you can ask, 'Do you want to keep this relationship? Do you want to integrate into the United States or do you want to become an independent state?'”