Tufts’ advising deans recently sent an email outlining steps students should take if they’re feeling ill this semester. One message was very clear: Students feeling sick should “Stay home!” The email, which also directed students to fill out a short-term illness form on SIS if missing class, came just in time. This is because I have had an illness scheduled for Friday, March 19, and Monday, March 22, for quite awhile now. If ever there is a time to feel a faint scratch in the back of your throat, a slight spike in temperature or a very mild stomach ache, it’s during the first and second rounds of the NCAA basketball tournament. And of course, during a pandemic, taking a symptom induced day off from class to watch twelve straight hours of basketball isn’t lazy or selfish, it’s noble.

The NCAA tournament is everything that’s great about sports condensed into three weeks of basketball. Rivalries, powerhouse teams, underdogs, comebacks, buzzer beaters — March Madness has it all. Since Magic Johnson and Michigan State defeated Larry Bird and Indiana State in the 1979 national championship, the tournament has become a staple in American sports. Many of today’s NBA stars first made names for themselves in the tournament. Think Carmelo Anthony at Syracuse in 2003, Stephen Curry at Davidson in 2008, Kemba Walker at Uconn in 2011 and Anthony Davis at Kentucky in 2012. But for every future NBA player and one-and-done superstar, there are many more rock solid upperclassmen playing their last basketball games in front of major audiences.

The tournament is known for the moments when all the stars align and something remarkable happens, so remarkable that you can’t quite believe your eyes. Christian Laettner’s buzzer beater off of a three-quarter-court pass from Grant Hill, Kris Jenkins’ 3-pointer to win the national championship for Villanova and University of Maryland Baltimore County becoming the first sixteenth-seeded team to ever win a game are a few moments that will always be part of the pregame Turner Sports tournament montages. The tournament is so exciting and so full of twists and turns that your eyes have to be glued to the TV from the time the first game tips off until the final buzzer sounds and the confetti starts falling. If you look away, even for a second, you could miss the moment you’re going to tell your kids about one day.

Jim Valvano was the architect behind one of the greatest moments and Cinderella stories in NCAA tournament history. In 1983, the North Carolina State head coach led his eighth-seeded Wolfpack to a championship victory over the dominant “Phi Slama Jama” University of Houston team that had cruised to the No. 1 overall seed with future hall of famers Hakeem Olajuwon and Clyde Drexler leading the way. NC State shocked everybody by beating Houston on a buzzer-beating Lorenzo Charles dunk, and Valvano hysterically running around the court looking for someone to hug became an indelible image in college basketball lore.

Ten years after winning the national championship, Valvano died of cancer. He was only 47 years old. Three months before his death, Dick Vitale helped Valvano slowly climb the stairs of the ESPY Awards’ (Excellence in Sports Performance Yearly Awards’) stage, where he proceeded to deliver an all time speech that has since been viewed millions of times. Valvano told the audience at Madison Square Garden that there are three things people should do every day: “Number one is laugh. You should laugh every day. Number two is think. You should spend some time in thought. And number three is you should have your emotions moved to tears,” Valvano said. “If you laugh, you think, and you cry, that’s a full day. That’s a heck of a day. You do that seven days a week, you’re going to have something special.”

Most people can find a way to laugh and think every day, but being moved to tears is less common. Coincidentally, it’s not "The Notebook" (2004) or A Great Big World’s “Say Something” (2014) that can consistently move me to tears, but rather the very tournament that made Valvano famous. It is the human element of a single elimination tournament featuring mostly 18 to 22-year-olds that makes the tournament such a unique event. Any single shot, foul, rebound or turnover can be the difference between a player’s childhood dreams coming true and suddenly crumbling to the ground on national television. The games aren’t just sports stories, they're human stories, and the margins between the glory of victory and the agony of defeat are razor thin.

In 2017, two of college basketball’s blue bloods, North Carolina and Kentucky, met in the Elite Eight. It was a thriller from the tip, and North Carolina won on a game-winning jumper by Luke Maye with less than a second left. After the game, De’Aaron Fox and Bam Adebayo, two of Kentucky’s best players, spoke to the press while literally bawling their eyes out. Through tears and with his arm around his crying teammate, Fox said, “I love my brothers, man.” The clip is enough to make anyone tear up. Moments like this are not few and far between in March. Every game has a loser, and on every losing team there are a number of players who will never again play for their coach or with their best friends and teammates. When people cry because something has ended, it means that thing had meaning. The brotherhood, the fierceness of competition, the momentum swings, the relationships with coaches — that’s what it’s all about.

But Valvano wasn’t just talking about being moved to tears in sadness. In fact, he said in his speech that it “could be happiness or joy.” In every tournament there are inspiring stories, underdog stories and comeback stories. The press conferences with winning players in March are just as likely to get the tear ducts going as the ones with the losers. On Saturday, Georgia Tech won the ACC conference tournament for the first time in nearly 30 years. Jose Alvarado, a senior guard on the Georgia Tech team that hasn’t made the NCAA tournament in 11 years, was interviewed by ESPN’s Holly Rowe after the game. “I wasn’t even supposed to be in the ACC. [Coach Josh Pastner] took a chance on me,” Alverado said. “I got my daughter in the stands, I got my dad. My family couldn’t make it because it’s just a struggle in life, but I’m just so happy I get the chance to tell them I’m a champion.”

After the game, one of my basketball teammates from high school texted me, “Georgia Tech man. Just watched the highlights and damn what a moment with Alvarado.” There are very few sporting events where fans can see and feel the meaning of sports on their TVs, and the college basketball postseason is one of them.

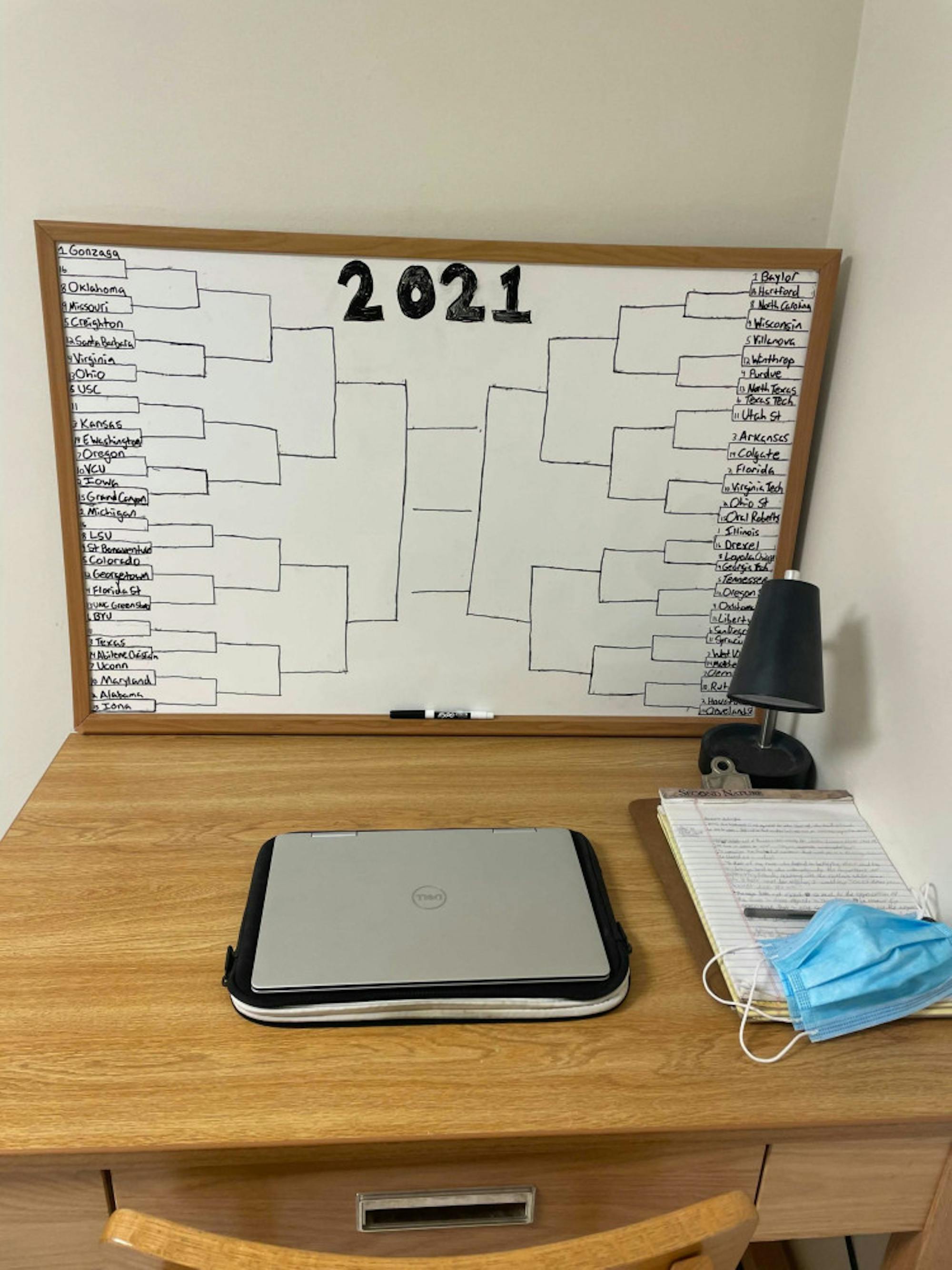

Every year in mid-March, around the time the spring weather starts popping, I go to my closet and grab an old whiteboard with bracket lines permanently drawn on. The spaces above the lines have faint smudges-remnants of past nail-biters and blowouts, deep runs and early round upsets. On Selection Sunday, I watch the last of the conference tournament games and then sit on the edge of my seat as the CBS crew of Greg Gumbel, Seth Davis and Clark Kellogg unveils the bracket. I take out a trusty Expo dry erase marker and slowly fill in the bracket as the first round matchups are announced. When the 68-team field is set, the white board is still just a blank canvas, but over the next few weeks the players and teams will paint a masterpiece. Let’s dance.