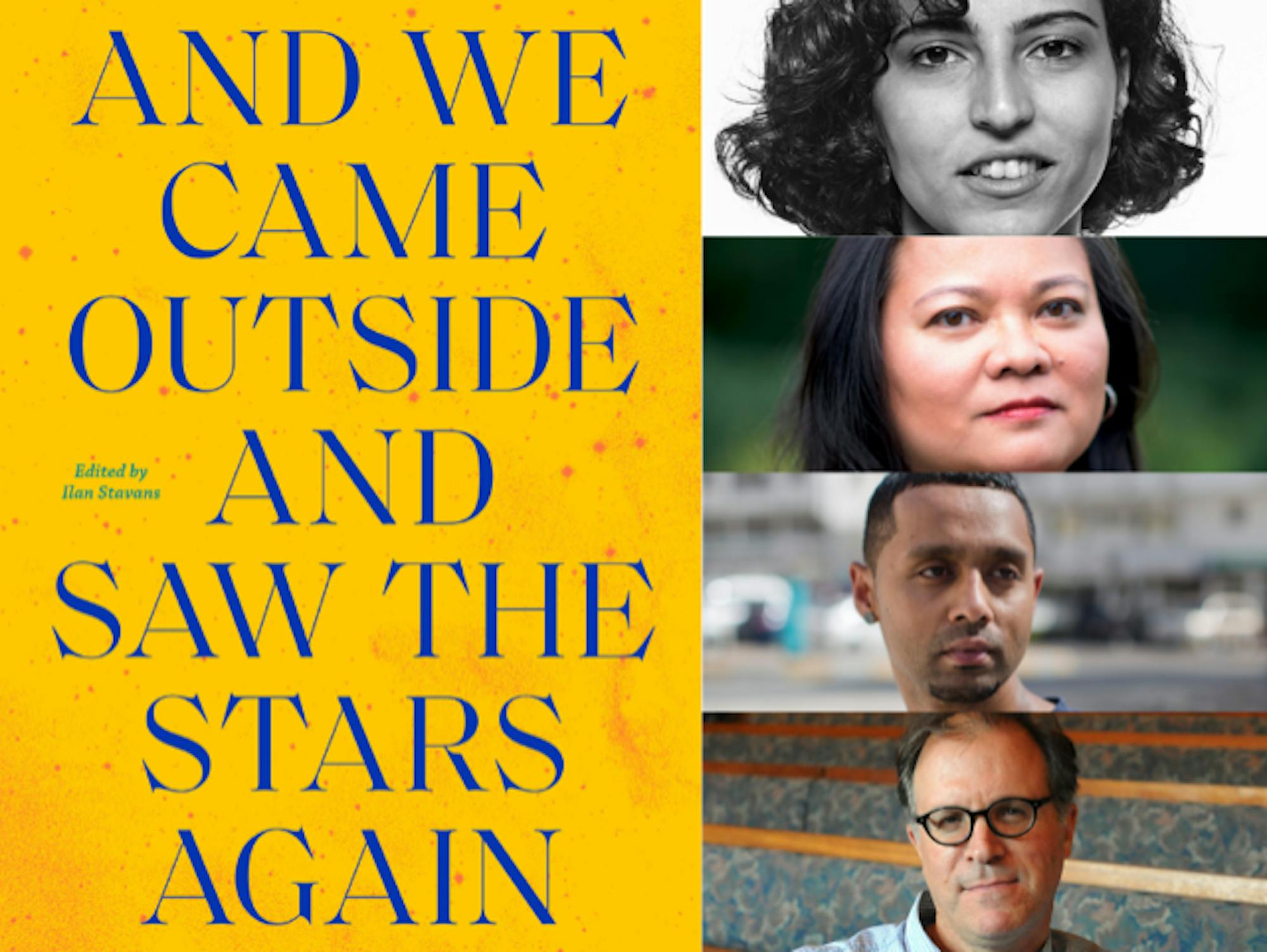

On Nov. 11, Brookline Booksmith hosted “Immigrant Writing in a Time of Crisis,” a conversation with Mona Kareem, Grace Talusan, Deepak Unnikrishnan and Ilan Stavans. Unnikrishnan is a writer from Abu Dhabi, whose book "Temporary People" (2017) won the inaugural Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing, the 2017 Hindu Literary Prize and the 2018 Moore Prize. Kareem, a poet and a Best Translated Book Award nominee, and Tufts alumna and author of New York Times Editor's Choice "The Body Papers" (2019) Talusan (LA'94) both contributed to"And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again" (2020) — an anthology of works describing how lives have been transformed by COVID-19. It is edited by Stavans, who is the publisher of Restless Books, a professor at Amherst College and has received a Guggenheim Fellowship.

The authors had incredibly valuable and diverse insights, ranging from the role of imperialism in language to the burdens of being labeled an immigrant writer.

Stavans, who is Mexican American, began the discussion by questioning how he conceptualizes the idea of a crisis.

“I used to think that the word crisis had been diluted … that the word no longer has any meaning. I don't remember, at any point in my life, however, being in a crisis like the one we are right now,” Stavans said.

And he was not simply referring to the pandemic.

“I am on the other side of the border in a country, the United States, where I thought the democratic institutions were solid, where political transitions were respected and respectable. Now, I find myself being arguably close to a banana republic in the very place that has been critical of banana republics,” he said. He then transitioned to ask the other three speakers, “What does the word ‘crisis’ mean to you now? How are you experiencing this moment?”

Talusan answered the question by acknowledging the emotional impact that the conceptual idea of a “crisis” can have on humans.

“A crisis is something very intense, and it's something that I just [try] to get through,” she said.

But there is something specific about the pandemic that has allowed for a certain endless tension to engulf our daily lives, and Talusan described that exact sentiment by acknowledging how descriptions of global chaos as an “ongoing crisis” have a distinct impact on our emotional health. Since March, Talusan has been trying to adjust to the pandemic and find ways in which she can distract herself.

“But then something else comes along,” she said. “And then it kind of tips the new normal.”Talusan concluded by saying that, through her immigrant identity, she has learned how to deal with these constant alterations of what is normal. In Talusan’s words, “getting destabilized and then figuring out a way to keep going” is what constitutes the immigrant experience at most times.

“We immigrants know crisis, we have at least a sense of being destabilized," Stavans said in agreement.

“The word ‘we’ is interesting, right?” Unnikrishnan said, instantly questioning the collectivity that can be naturally imposed onto identity groups. Even so, he identified with Talusan’s comment. “[As immigrants] we were forced to be resilient for most of our lives … but then there's also hope, at the end of the tunnel ... you're hoping for something that you can really latch on to,” he said.

But with COVID-19 he has had a hard time finding hope in this ongoing, seemingly never-ending, crisis.

“I just want to hug people,”Unnikrishnan said with a saddened laugh. “I think we're all trying and we're coping, and we're mad and tired. So for me, that's what ‘crisis’ is … we're doing the best we can and, sometimes, this is the sobering part: That isn't enough."

Stavans then prompted Unnikrishnan to discuss what exactly the role of the writer should be during a crisis: Should they be documenting the present or waiting to write reflectively on the past?

“Because I work in academia, the word ‘productivity’ gets thrown around a lot. And I have a great deal of respect for the word but now I just want to burn it if I'm being completely honest,” Unnikrishnan said. “What I'm doing is I'm observing.”

Kareem reflected on her role as a poet during this time of crisis.

“I was never the poet who is able to reflect on the current moment, I never concerned myself with that … the current moment really occupies me,” she said.

Kareem added that the world has reflected her crisis for the very first time. She is an asylee living in the United States who has not seen her family for almost 10 years. After the pandemic hit and people began to talk about the value of family, their plan B and what safety means to them, she saw people experience what she has had to live with for nearly a decade.

“All this time living as an immigrant I tried to be temporary,” she said. “I tried to be easy to move around … no attachments,” she said.

But during this time of seemingly endless crisis, she has decided to root herself, to find some sort of geographical connection.

Apart from the actual role of being an immigrant writer, it is also important to consider the implications and significance of the label itself. Talusan described how she only started calling herself an immigrant writer after winning the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing.

“I'm in such a place of privilege that if I could do anything with any of my writing as an immigrant writer, I'm happy to do it," she said.

Unnikrishnan differentiated “immigrant” from “writer.” First, he pridefully advocated for the powerful existence of the immigrant. When someone uses “immigrant” in a negative way, he answers, "Bring it. Yes, I am … I'm not ashamed of it … I embrace that.”

He explained that the issue he has with the moniker is related to the “writer” part of the expression.

“Individuals may feel as though immigrant writers can only write about the immigrant experience,” he said. “I am an immigrant writer … Do I only write about immigrant things? No, it's not an aisle at the supermarket. You can’t compartmentalize all of us. That’s why context is important.”

Stavans concluded that “The only thing that matters to me as a reader is the humility and authenticity that can come across in the page ... No matter how you have dismantled language for the rest of us to enjoy, if you have dismantled it with care and conviction in an authentic and humble voice, then that message is going to come across … I just love the fact that writers take that leap of faith. Their work has fallen on some of our ears and we are better as a result.”