Content Warning: This article contains mentions of antisemitism.

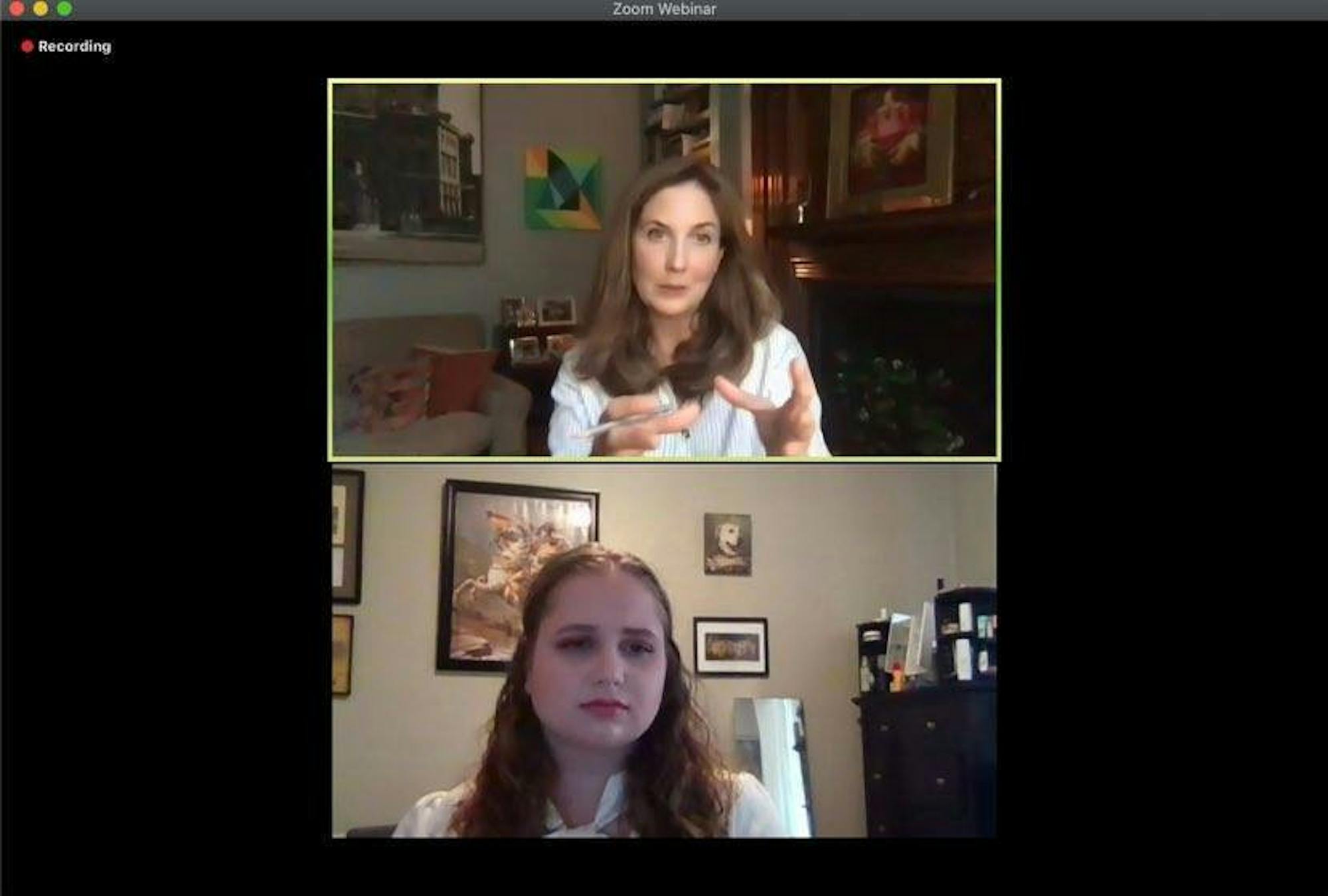

“This book is not a history book,” Tufts alumnaAriana Neumann (LA '92) said at the onset of her Sept. 30 webinar. The event was organized as the first History Alumni Authors Series presented by the Tufts History Society and Tufts University Department of History. The subject was her2020 New York Times Bestseller "When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains," which haswon her international acclaim. The book tenderly describes her journey of discovery and reconciliation with the history her father had kept secret for decades.

Neumann, who graduated Tufts in 1992 with a Bachelor of Arts in history and French literature, didn’t know her family history until after her father’s death in 2001. She described in Wednesday’s webinar the childhood curiosity and amateur sleuthing that shaped her.

“I didn’t know that the biggest mystery I would solve would be that of my father,” she said. Neumann retold what it felt like to grow up in Caracas, Venezuela with a father who was “so engaged in the present and so excited about the future he never really spoke about the past.”

And yet, Hans Neumann’s past was more complicated than his daughter had ever expected.

Born to aJewish-Czech family in the decades before the Nazi occupation of Prague, Hans Neumann was forced to outwit the Gestapo as his family was moved to concentration camps. The book follows Ariana Neumann’s accounts of the hours she spent poring over old Czechpolice and tax records as she pieced together her family’s story. Slowly, as the picture of her family's history became clearer, she tells how she decided to compile her findings into a book. During the webinar she said, “I slowly realized that if I didn’t tell these stories, these stories would die with me.”

The stories she tells are remarkable. Her father escaped the Gestapo three times while living in Prague until the spring of 1943, when he went into hiding inside a makeshift 6-by-3 footroom inside his family-owned paint factory for three months. Hans Neumann later fled Prague with his friendZdenek’spassport and took the train to Berlin, where he would live undercover with Zdenek as a chemist under the Nazi Party for two years.

Reading from her book, Ariana Neumann shared her father’s firsthand account about his fateful train ride from Prague to Berlin. With Zdenek’s passport in his pocket, and a cyanide pill tucked behind his molar should he be discovered, Hans Neumann documented the journey and later placed the accounts in the box he left for his daughter.

When Ariana Neumann decided to undertake a similar train ride along the same route 75 years later with the papers her father had written clutched in her hands, she wrote in her book, “I hope that he felt me cradling him, holding his hand across a world of time and experience.”

Neumann’s is a story about bridging historical gaps and finding the threads that bind us across generations, as she explained in her webinar. Describing her love for history, Neumann said, “numbers and dates never moved me … what really moved me tended to be the human experience.”

She also told of how this love was realized while attending Tufts. “I studied history to not repeat the mistakes that were made in the past,” Neumann said. She continued in a rather sentimental tone, stressing that to do so “we have to retell history in a way that appeals to as many people as possible.”

In the second portion of the webinar, senior Phoebe Sargeant, president of the Tufts History Society and a history major, posed some questions to the author. When asked how the Holocaust affected her, Neumann responded that “trauma, even when it’s silenced, trickles down all the same.”

Hans Neumann’s story is not the only one to go untold. Countless lives and countless histories are buried in the depths of time and experience through which Ariana Neumann herself searched. As numerous and diverse as those histories may be, Neumann has urged us through her writing and her Tufts webinar to consider that “we have to find what it is that binds us and celebrate it, rather than what separates us all from each other.” And, at least for Neumann, looking to the past was the best way to tighten the threads that bind her to the present.