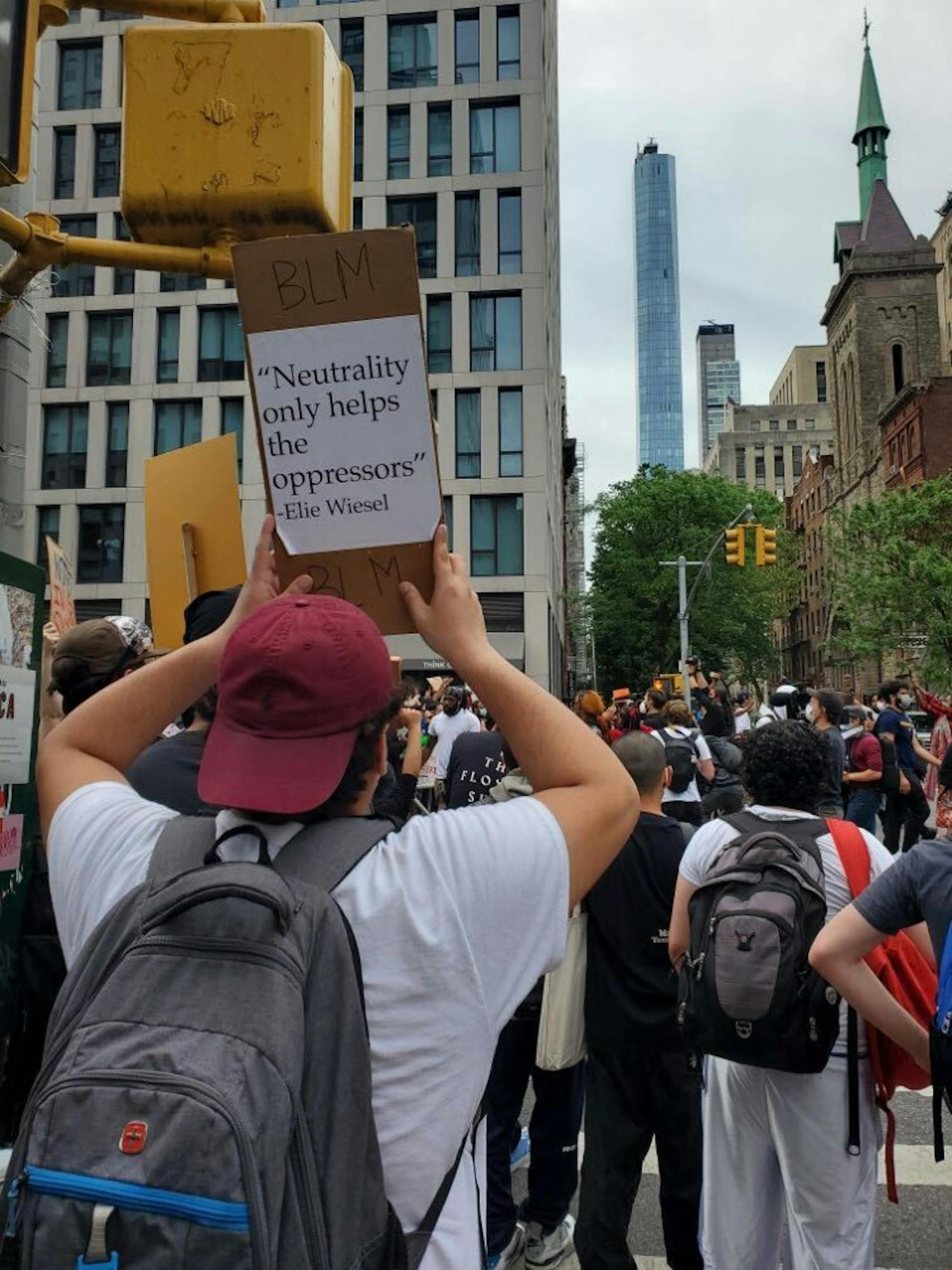

Manhattan, New York City

“You’re one of the good ones,” an officer told one of Cara Hernandez’s friends in high school after checking their school ID. Hernandez, who is African American and Puerto Rican American, and her friend, who is African American, attended a private school in the Bronx. To Hernandez, the implication was clear.

“There are no ‘good ones,’”Hernandez, a rising senior, said about the incident. “The worth of a black life is not to be determined on their income, on their merit, on their profession or on their education level. A life is a human life.”

Acts like the one Hernandez witnessed are not isolated incidents. For centuries, black individuals and communities have been subjected to profiling by police and police violence. The nationwide protests that have carried on for more than two weeks are about more than Floyd’s death. According to Hernandez, they’re about the broader trends in the criminal justice system that adversely affect communities of color.

“In racist cases, it doesn’t matter how ‘smart’ you are or who you’re related to,” Hernandez said. “You’re still seen as another black person.”

On June 2, Hernandez joined a demonstration of more than 1,000 people in lower Manhattan. The protest kicked off the sixth straight day of protests in New York City and was the second night of an 8 p.m. curfew imposed by Mayor Bill de Blasio. Hernandez arrived at 12:30 p.m. wearing gloves and a mask to protect against COVID-19.

“It would be easier to not get involved,” Hernandez, who is a diversity and inclusion officer for a sorority on campus, said. “But I have a stake in the conversation.”

The protest’s organizers told the crowd repeatedly during its march northward to avoid confrontations with police, a handful of which were wearing helmets or holding riot shields, according to Hernandez. Although interactions remained minimal, she said the atmosphere was tense with the presence of police and the frustrations voiced by protesters about law enforcement and its discriminatory practices.

When there were exchanges between police and protesters, organizers of the protest stepped in to neutralize the situation. Hernandez said these exchanges stuck with her the most after the protest.

“The organizers mentioned purposefully, again and again, to keep the protest peaceful, to not engage with the police,” Hernandez said. “The organizers who got in the way told protesters to step away for their own protection, saying ‘do not give [the police] a reason to engage; they’re searching for a reason.’”

Hernandez wants to see the four officers involved in Floyd’s death convicted, hoping it would lead to more accountability for police officers on the local level. On the national level, she is urging the formation of an independent committee to review incidents of police violence.

“I think the establishment of an independent organization or committee that is tried and just and true to examine these cases and to hold people to the fullest sense of the law, regardless of their status or profession, would be a great start,” Hernandez said.

Derek Chauvin, the officer who killed Floyd by kneeling on his neck for more than eight minutes, has been charged with second-degree murder by Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison. The other three officers are charged with aiding and abetting the death of George Floyd.

Washington, D.C.

The protests in Washington, D.C. have garnered special attention after hundreds of demonstrators were forcibly dispersed by the police on June 1 so that President Donald Trump could appear at St. John’s Episcopal Church to pose for photographs with a Bible.

Alex Healy, a rising sophomore from Washington, D.C., was in the crowd protesting when demonstrators were cleared.

“The distance between the police and the crowd was about two inches when they started firing rubber bullets at us, when they sprayed us with tear gas, when they came at the crowds, because President Trump was four blocks away, walking to St. John’s Church, which was in the area where we were protesting, for his photo op,” Healy said.

Healy has been involved in several days of protest to support the Black Lives Matter movement since the death of George Floyd. In her experience, she said the protests have remained mostly peaceful during the day with violence more likely to occur later at night. The violence incited by the police on June 1 was out of the ordinary.

“That was the only day that Trump’s been in D.C. That was definitely the most violent day, that was when all the federal police, the military, National Guard, had been called into D.C. specifically for these protests,” Healy said.

The dispersal of the crowd, which Healy was a part of, inspired Aliya Magnuson, a rising sophomore from Burke, Va., to travel into the city and take part in a protest the following day.

“It just made me so mad to see what had happened the day before, how protesters were tear gassed for peacefully being there, and Trump using the church on that street as a photo op," Magnuson said. "That made me really upset, and so I wanted to show my support.”

Magnuson, who was protesting outside the White House near Lafayette Park from midday to about 6 p.m. on June 2, said there were some increased security measures taken by the police, like putting up large gates around Lafayette Park and pushing people farther away from the White House than they had done the day before.

Magnuson said all protesters remained peaceful and regarded these measures seriously.

“Everyone just backed up and was very respectful," Magnuson said. "As it got closer to the curfew time, everybody kneeled down and was quieter."

Likewise, in Healy’s experience, the fear of violence in attending protests has come from the police, not other protestors.

“It’s 100% because of the police, not because of protesters, that I ever feel unsafe," Healy said. "It’s because at any second, I have absolutely no idea what they’re going to do."

Magnuson addressed her role in these protests and what it felt like to be a white person on the streets.

“We just all knew we were fighting for the same thing,” Magnuson said. “I could tell people were excited to have allies there too.”

Similarly, Healy said she sees the protest as a small part she can take to be involved in an issue she’s passionate about. Healy said growing up in the primarily black city of Washington, D.C. has shown her what systemic racism by the police and by other institutions looks like.

“When it comes down to it, there’s a huge change that needs to be made,” Healy said. “It’s about abolishing the police state; it’s about defunding, demilitarizing the police state; it’s about making actual change on the policy level, at a rate that needs to happen a lot quicker than it has been.”

This moment of movement and protest comes at a unique, unprecedented time in history, with the threat of COVID-19 still looming large and strict social distancing still encouraged.

Magnuson and her mother, whom she attended the protest with, weighed this threat in their decision to go into the city but decided the risk was worth the importance of the action.

“Ultimately, we thought that this issue deserved our attention,” Magnuson said.

Magnuson and Healy both reported everyone wearing masks and staying separate whenever possible.

Healy acknowledged the consideration of COVID-19 in her decision as well, coming to the same conclusion as Magnuson.

“I think it’s so crazy that in the middle of a pandemic, the black community has to go out in the street and break social distancing like this to advocate for their lives,” Healy said. “For me, it’s a much larger issue that I have the privilege to not have to live my life that way. So I really don’t think that there’s any excuse for me personally to not be out there.”

Hampton, N.H.

When rising sophomore Abigail Wool learned of an opportunity to make a difference, she was all in. Over the last week, she’s been busy organizing the Seacoast March for Justice in response to the death of George Floyd and the centuries of systemic racism that enabled it.

The march took place on June 6 and was the third justice-related event Wool attended that week. The first two were on June 1 — one a protest, the other a vigil.

“I saw the posts and I was like, ‘Alright, looks like that's what I'm doing today,’” Wool said, referring to Facebook posts promoting the events she attended.

She wore a mask, practiced social distancing and prioritized what she described as her “moral duty as a very privileged white person in our country to follow the lead of the black and [people of color] community leaders and learn how to stand with them instead of sitting in complicit agreement with the broken system.”

The first of the two events was a peaceful protest of about 100 people in Hampton, N.H., all of whom encircled speakers and listened to a speech from 60 years ago that, in Wool’s words, “still holds relevance, sadly.” Afterward, police officers knelt alongside protesters in what has become a stance of solidarity and against police brutality. Despite the protest being unstructured and slightly disorganized, “it was still a really powerful moment,” Wool said.

On the same day, she attended a candlelight vigil in Dover, N.H. with over 2,000 people. There was chanting, followed by silence; candles burned amid a dark sky.

Wool expressed solace in being surrounded by like-minded people.

“It was really beautiful, and it helped us remember why we're doing this and the reason behind it all,” she said.

A police helicopter hovered above both events, the goal being to keep peace, according to Wool. She described it as a “looming presence,” nonetheless.

And in Hampton, two men were openly carrying, which, Wool admitted, made her a little uneasy. She felt safe at both events, though.

Since then, Wool, rising sophomore Isabelle Woollacott and community members in their respective municipalities planned the Seacoast March for Justice and a car procession from Kittery, Maine, to Portsmouth, N.H., two bordering towns.

“In light of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the centuries of racial injustice in this country and around the world, we are hosting a peaceful, youth-lead protest in this community to show our solidarity and support,” the event’s Facebook post reads. The Facebook event indicates that 423 people attended the event.

The march’s leaders hosted a Zoom call prior to the event — it served as a space to make signs, t-shirts and conversation about “racial injustice, white privilege, white supremacy, and steps forward,” according to the Facebook post.

For Wool, protests are central to American identity.

“Protesting is a huge part of free speech and what makes America unique,” she said. “It’s the first step toward impactful change.”

Atlanta, Ga.

“We’re not the only ones fighting for rights,” Nyah Ebanks, a Caribbean American and rising sophomore, said. “It's a lot of other races that are coming together and are noticing the injustice that's happening in our country.”

That was the message that Ebanks took from a peaceful protest she attended in downtown Atlanta on Wednesday. In addition to signing petitions and donating to Black Lives Matter, George Floyd’s family’s GoFundMe and a fund that helps bail out arrested protesters, Ebanks felt compelled to march for others, and for herself.

“I felt like I had to protest, I needed to go out and show that I was supporting,” she said.

Wearing a mask, as were others around her, what Ebanks was most nervous about was gaining her mother’s permission.

“I was so nervous to ask my mom,” she said, hoping COVID-19 concerns would not inhibit her plans.

Ebanks’ mother was supportive, encouraging her to protest.

“[My mom said] ‘I’ve protested before, and I definitely think you should do it,’” Ebanks said.

In explaining her motivation, Ebanks vocalized a grim thought, one that is shared by many.

“A lot of times I just think, ‘What if it was my father next? What if it was my mother next? What if it was my sister next?’” she said.

Ebanks channeled this emotion as she chanted and walked around the Olympic rings statue in Centennial Olympic Park on Wednesday. Citing strength in numbers, she went with a friend.

And numbers there were — Ebanks was one of at least several hundred who marched along and chanted “justice for George Floyd.” She recalled passing an artist painting a mural of Floyd over a graffitied wall. Others, including representatives from Black Lives Matter, distributed water and free meals.

According to Ebanks, boarded-up windows and broken glass were the only signs of violence — they were the remnants of previous nights of protests. Though she remained “on guard,” Ebanks felt mostly safe amid a large group.

“[The police] were only there to control everything and to guide us through our walk,” she said. They also stopped traffic to let protesters through.

At one point, when the mass of protesters approached a blockade of police, one of the organizers stepped up and called on non-black individuals to step in front.

“I immediately saw a whole bunch of people who were white, Hispanic, they all ran to the front,” Ebanks said.

In doing so, they shielded black individuals, who have been historically brutalized by police, from the blockade.

“Seeing that really moved something in my heart because it really made me think, ‘We’re not the only ones that are fighting for our rights ... it’s a lot of other races. They’re really ready to sacrifice for us,’” Ebanks recalled. “And that really just made me happy.”

Chicago, Ill. and New York, N.Y.

Even for those who feel passionately about the Black Lives Matter cause, protesting is not always the obvious, or even possible, choice.

Although the protests going on all around the country, and now the world, are to honor the death of George Floyd and stand up to the racial injustice black people face at the hands of the police (and many other systems and institutions), there is still an element of privilege in who gets to participate.

Waideen Wright, a rising sophomore from Chicago, Ill., who identifies as black, spoke to the high stakes that already-marginalized individuals face when deciding whether they want to publicly participate in protests.

“One big factor that keeps minority activists away from protests is the possibility of getting arrested,” Wright wrote in an email to the Daily. “Transgender people fear that they will be arrested and their identity outed in an unaccepting environment. Low-income students fear losing scholarships and certain government aid after an arrest. Black single parents fear being arrested and leaving their kids, for maybe a night or maybe forever.”

Black protestors are more likely to face severe consequences if they are arrested, something that non-minority activists don’t have to take into account.

Wright said she has felt sad, angry, frustrated and proud of the protests happening across the world in the past week, but she herself has not participated. Wright said she has prioritized checking in with her black friends and family and making sure they are doing well and taking care of themselves, exemplifying a different form of action that doesn’t require taking to the streets.

Wright noted that not everyone has the option or desire to be out in the streets, but that doesn’t mean they can’t take part in activism.

“I’ve been donating, signing petitions, and making information on other productive solutions available to friends and family,” Malcolm Cox, who is black and from New York City, wrote in an email to the Daily.

Cox, a rising sophomore, has not attended a march, mainly due to safety concerns around COVID-19, but he is still involving himself in the movement from home.

“I’m evaluating all the ways I can make sure my voice is heard even if I don’t attend a march,” Cox wrote.

Both Cox and Wright are encouraged by the number of people joining protests in person and by those participating in their own ways.

“The support that I’ve seen from other communities is comforting, and I am eternally proud of the strength and persistence of my people,” Wright wrote.

Cox said he felt similarly, and also feels these protests could advance the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Because the circumstances of George Floyd’s murder are so violent and the video evokes such strong emotions, it seems as if more people are actively joining the movement for change than before,” Cox wrote.

For Cox, this moment of protest could pave the way toward an evolving future and hopefully even be the last of its kind.

“In order for racial injustices to end, our newest generation has to be taught differently,” Wright wrote. “A system of injustice cannot be changed until the problems are actively seen as unjust in the eyes of those who benefit from it.”