Rumors have recently been circulating surrounding the release of a third film in Disney’s “National Treasure” (2004–2007) series after The Hollywood Reporterwrote that writer Chris Bremner had begun work on a script for “National Treasure 3.” The prospective new release traces its roots back to Disney’s 2004 film “National Treasure” starring Nicolas Cage, in which protagonist Ben Gates (Cage) undertakes an epic quest in search of the treasure of the Knights Templar which, according to a cryptic message passed down through his family for generations, lies hidden in the United States. Gates, along with tech-savvy sidekick Riley Poole (Justin Bartha) and obligatory love-interest Dr. Abigail Chase (Diane Kruger) races against gluttonous treasure hunter Ian Howe (Sean Bean) and the FBI to steal the Declaration of Independence, which Gates believes is encrypted with an invisible map revealing the treasure’s location to whoever is clever enough to crack it.

As these two parties race to the finish line, the Declaration itself plays an integral role in the action. Its value is immeasurable and multifarious: both an instrument and a symbol, it’s at once a clue, a bargaining chip and a precious national heirloom. The struggle for possession of the Declaration lands the document in a slew of remarkably precarious situations.

For starters, the Declaration is shot at multiple times with a gun. Additionally, the original manuscript of the philosophical scripture of American liberty suffers treatment analogous to the daily routine of a stereotypical young adult female: anointment with essential oils (lemon juice), a bout with a blow dryer and a trip to Urban Outfitters. The horror endured by the 243-year-old piece of parchment prompts important questions: could the Declaration of Independence actually take such a beating? Incredibly, in the 15 years since the film was released, it seems that no one has undertaken an answer to this question. That ends today.

Cage wouldn’t be the first person to manhandle this pioneering treatise of liberty; the Declaration of Independence is actually in such poor condition that it’s practically illegible. It owes its sorry state in part to the vicissitudes of history. From the day it was drafted on July 4, 1776, the Declaration was constantly on the move. According to the National Archives, it would have been touched, rolled, unrolled and compressed countless times during our nation’s infancy, which “took its toll on the ink and on the parchment surface through abrasion and flexing.” It finally settled down in Washington, D.C. after the War of 1812, but before long a new threat emerged: mass-market publishing. As early as 1817, widespread demand for copies of the Declaration left the document in disrepair. The prevailing method at the time was to make “press copies,” which involved pressing a damp cloth onto a manuscript to remove some of the ink from the original, and then using the freshly inked cloth to make copies — think along the lines of placing Silly Putty on a newspaper. It is unknown whether this buckwild procedure was ever performed on the Declaration of Independence, but it would explain the rapid degradation of the document less than a century after it was penned.

In 1841, the Declaration was hung in a new building — today the home of the National Portrait Gallery — at the behest of Secretary of State Daniel Webster, where it remained for the next 35 years. After more than three decades of direct exposure to sunlight, humidity and temperature fluctuations, people began to remark on the sorry state of the document. One commentator in the Historical Magazine in October 1870 warned that "[t]he original manuscript of the Declaration of Independence … [is] rapidly fading out so that in a few years, only the naked parchment will remain. Already, nearly all the signatures attached to the Declaration of Independence are entirely effaced." These and other scathing remarks finally moved government officials to prioritize the document’s conservation. After 1921, the Declaration was kept in the Library of Congress before moving in 1952 to its current home at the National Archives. Today, it is displayed in an aluminum and titanium case filled with argon gas, which maintains a relative humidity of 40% and a fixed temperature of 67 degrees Fahrenheit.

As far as “National Treasure” is concerned, history could only get us so far, so we decided to do some research of our own. In watching the original “National Treasure” and cataloging every tribulation to which the document is subjected, four classes of misconduct directed towards the Declaration of Independence emerged: impact, contact, exposure and storage-related crimes. From there we brought the results to the Tufts Digital Collections and Archives office in Tisch Library, where Collections Management Archivist Adrienne Pruitt helped us to sort out the fears from the fiction. We also contacted Christopher Barbour, the library’s curator of rare books and humanities collections librarian. Both had a lot to say about the film’s dubious archival practice.

Surprisingly, the myriad forms of vigorous jostling the document experiences — including but not limited to being shot at three times in its case with a handgun — don’t represent the most serious threat to the Declaration in “National Treasure.”

“General movement of the document isn’t so much of an issue — we carefully move our documents into the reading room for researcher[s to] use all the time,” Pruitt wrote in an email to the Daily. “Worse than jostling or high-speed chases or even being thrown into the street would be rolling and unrolling of the document.”

When storing parchment documents, consistency is key. The more inconsistent the position of a document relative to itself, the more likely the parchment is to be damaged. That being the case, when the treasure-hunters unfurl the Declaration in Independence Hall, they don’t realize they’re repeating history in more ways than one.

“It was the rolling, unrolling, and folding of the document that led to much of the original damage, visible as early as the 1820s,” Pruitt wrote.

Barbour added in an email to the Daily that while the parchment could likely survive careful rolling, the “protective” plastic film in which it is carried throughout the movie actually does more harm than good.

“Parchment is a durable material, and a document normally kept in sound, archival conditions probably could survive being rolled in a tube, if not tightly,” he wrote. “However, only a very high class of thief could be expected to employ a plastic enclosure of archival rating appropriate for the material to be stolen, acquired from a recognized dealer of conservation supplies. I fear that most thieves would resort to ordinary food-grade plastic wrap, (awful stuff, destructive to documents of any kind), or something from the hardware store.”

Ben Gates may not be your average cat burglar, but you wouldn’t know it from the plastic film he uses, which looks like he grabbed it off the floor of Michael’s Arts & Crafts.

Hidden danger also lurks in the air itself. “[R]emoving [a document] from a climate-controlled environment and then subjecting it to further mechanical stresses would cause much further damage” than frequent motion, Pruitt said. Much of this danger owes to the delicate constitution of the parchment itself.

“[P]archment documents are complex objects; there is the writing support — the parchment itself, which varies in quality, and through such variation may react differently to changes in conditions; also ink, often pigments, and possibly seals," Barbour wrote. "An ideal relative humidity for storage strikes a balance good for all these materials, in order to maintain the strength and flexibility of the document.”

Considering the different climates to which the Declaration was exposed in “National Treasure,” it is safe to say that the parchment would not have been left unharmed.

Complex considerations aside, however, Barbour emphasized that “in every case, stability of conditions is a good thing, and variation is bad.” Pruitt added that “[c]limate-controlled environments are very important for archival documents, because fluctuations lead to actual changes in the dimensions of the materials, and too much of that leads to degradation.”

Had the film’s so-called historians done their research, they would have felt this concern acutely. Popular Mechanics reports that conservationists of the Declaration realized in the 1940s that the fluctuating humidity of Washington, D.C. had created tears at the edges of the document, which grew over time. In the wake of this realization, “exposure to air suddenly became public enemy number one.” Indeed, exposure to open air can cause severe damage to parchment in just moments.

“A sheet of parchment can curl within minutes in a warm, dry room,” Barbour wrote.

Conversely, “[e]xposure to air that is too moist opens the door to biological attack, by mold and other agents; this can happen quickly,” Barbour wrote.

In light of this, carrying the Declaration into a labyrinth of underground catacombs probably wasn’t a good idea.

Of course, that’s not the only kind of exposure threat faced by the Declaration. In an attempt to reveal a hidden message on the back of the document, Gates and Dr. Chase douse the back of the parchment in lemon juice, and then proceed to heat the parchment first with their breath and then with a hair dryer.

“Aside from the fact that their chemistry regarding invisible inks is highly questionable, obviously exposing parchment to an acid like lemon juice and then to heat is an extremely bad idea that would make the parchment even more brittle,” Pruitt wrote.

This painful scene essentially amounts to a production misstep: the Declaration appears unharmed after this act of archival sacrilege.

Cage and company make yet another mistake in the film — two times over. When first removing the Declaration from its case and once more while accosting it with citrus, the Declaration is handled with gloves. Pruitt made it clear that gloves are a no-go when handling a document like the Declaration.

“Touching parchment with clean, bare hands is actually the preferred method,” Pruitt wrote. “Wearing gloves — especially cotton gloves — can worsen dexterity and removes your ability to feel what kind of shape the material is in. You might accidentally use too much force because you can’t feel the page accurately and accidentally tear it, or you might drop a book because the gloves make you clumsy. Gloves also easily transfer dirt.”

So dire is this transgression that it’s painful for experts to witness.

“I promise you, every archivist who watched them handle the document with white gloves winced internally,” wrote Pruitt.

According to Pruitt, The Library of Congress recommends glove-free hands for handling parchment. Even when the treasure-seekers abstain from wearing gloves, they are not off the hook in the eyes of an archivist; natural oils and dirt accumulate on hands, and not once did a character perform the sacred art of ablution.

We thought our notes had covered everything, but Pruitt observed yet another way in which the film’s archival practice defies reality.

“[O]ne of the more unrealistic aspects [of the movie] was the depiction of a young woman as the Archivist of the United States: although we’ve had two acting Archivists who were women, the permanent Archivists of the United States have all been older white men,” Pruitt wrote.

It is fair to say that although “National Treasure” tells an exciting story with just the right amount of fantastical fiction, the unrealistic portrayal of historical artifacts pushes the plot over the edge from believable fiction to pure fantasy. Disney: next time, talk to an archivist.

Debunking 'National Treasure' through the eyes of an archivist

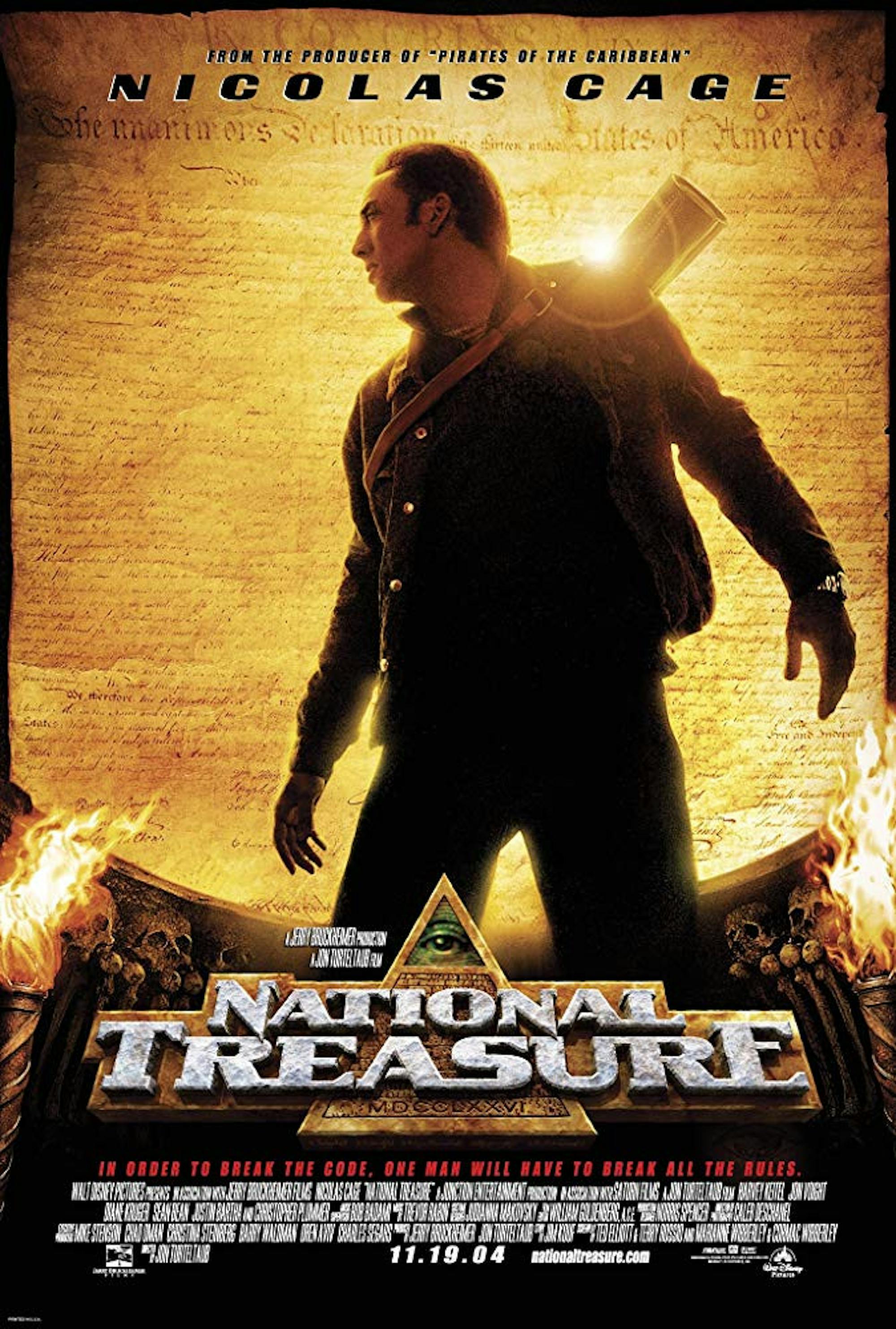

A promotional poster for "National Treasure" (2004) is pictured.