Released on Feb. 5, “The Wandering Earth” (2019), China’s debut sci-fi film spectacle, is now playing in Boston. The film was adapted from a novella of the same name by author Liu Cixin, winner of numerous prestigious sci-fi awards within and outside China, such as the Galaxy Award, the Locus Award and the Hugo Award. “The Wandering Earth” tells the story of Earth’s human-facilitated migration to a distant planetary system by the force of thousands of engines in an attempt to flee its otherwise imminent demise due to the expanding sun. The film alternates between the setting on earth and on an international space station, reflecting the “Interstellar" (2014) father-child dynamic in the relationship between Liu Peiqiang (Wu Jing) and Liu Qi (Qu Chuxiao) while exploring themes pertinent to the human identity and citing stylistic influences from western sci-fi films.

The young adult Liu Qi and his adopted sister Han Duoduo (Zhao Jinmai) exemplify the typical “child hero” trope in fantasy fictions as they literally save the world by respectively devising the plan to ignite Jupiter and recruiting global support. As the film approaches its end, the United Earth Government desperately declares that Earth will imminently crash into Jupiter due to its heavy gravitational pull, and that “the Wandering Earth” project has failed. As the whole world falls into heartbreak, Liu Qi recalls a childhood memory of star-watching with his father and learning from him that Jupiter is composed of primarily hydrogen. This nostalgic, involuntary act of remembering quickly leads to Liu Qi realizing that Earth might have a last shot at survival with the help of an ignited Jupiter, which will blow Earth to safety. Although Liu Qi comes up with this plan, his sister Han Duoduo helps execute it by broadcasting their message to the world and enlisting global support.

Portraying Liu Qi and Han Duoduo as world saviors who allow the continued existence of Earth, the film employs the narrative motif of the youth as both the literal and the symbolic path to the future. Indeed, adolescence is arguably the perfect liminal space that embodies both the inventive and exploratory tendencies of childhood and the power and agency of adulthood. Therefore, such a courageous, creative and idealistic generation is portrayed as the regenerative force within the society.

The film generally emphasizes the triviality of earthly existence by constantly bringing into sight beautiful, melancholic scenes of a helplessly lonely Earth wandering among the endless cosmic darkness and the image of a Jupiter-filled sky. As seen from a human’s perspective, the thrusters are powerful mammoths that project strong, sky-piercing blue flames into space. However, when the perspective shifts into one that watches Earth from space, as constantly occurs during the film, the once-majestic flames appear so faint that their efforts in propelling Earth seem no greater than what strands of hair can do to move a lead ball. What adds to the desolation of these space scenes is that the flames — ice blue in color and airy and soft in texture — assume a watery quality. The Earth seems to be shedding tears as it leaves behind evanescent traces of itself while moving forward.

Toward the end of the film, as Jupiter’s gravitational pull on earth grows, the sky, as seen on Earth, becomes almost entirely a misty view of the gaseous, monstrous-looking Jupiter. The sky’s loss of its original boundless height and endless space to the approaching leviathan of Jupiter triggers a suffocative sense of megalophobia in the audience, dwarfing their existence.

“The Wandering Earth” also uses the cliché of a dystopia controlled by artificial intelligence (AI), to indicate that human sentimentality should be more treasured than logic. In the film, MOSS, the AI operating system of the international space station, overrides Liu Peiqiang’s order to sacrifice the station as the fuel for igniting Jupiter, hence saving Earth. More often than not, AIs have been made self-conscious and rebellious in sci-fi films. Obvious prototypes for MOSS include the commanding system HAL 9000 from “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968) and the Autopilot from “WALL-E” (2008).

In “The Wandering Earth,” the space station carries countless human, plant and animal embryos and comprehensive records of human civilizations. Therefore, the reasoning behind MOSS’ choice is that it is highly cost-ineffective to sacrifice the recorded history and future of human existence to rescue an already-damaged Earth population with minimum likelihood of success. Therefore, MOSS differs from its predecessors on screen, in that it is essentially not anti-human, but anti-sentimentality and pro-rationality. The final defeat of MOSS serves as an endorsement of the human race as defined by its present existence, not its inanimate past or unknown future.

Despite inevitably drawing inspirations from Western sci-fi films, “The Wandering Earth” is unmistakably Chinese. Much of the film is set in Chinese cities, showcasing landmark architecture, like the CCTV headquarters in Beijing and the Oriental Pearl Tower in Shanghai, albeit in dilapidated forms. Besides, the protagonist Liu Qi, unlike some of his light-hearted, young parallels in the West, such as Peter Parker from the “Spider-Man” series, remains solemn and taciturn throughout the film. This introspective personality of Liu Qi reflects the generally more reserved Chinese culture in comparison to its Western counterparts, namely American pop culture.

'The Wandering Earth': China enters space on screen

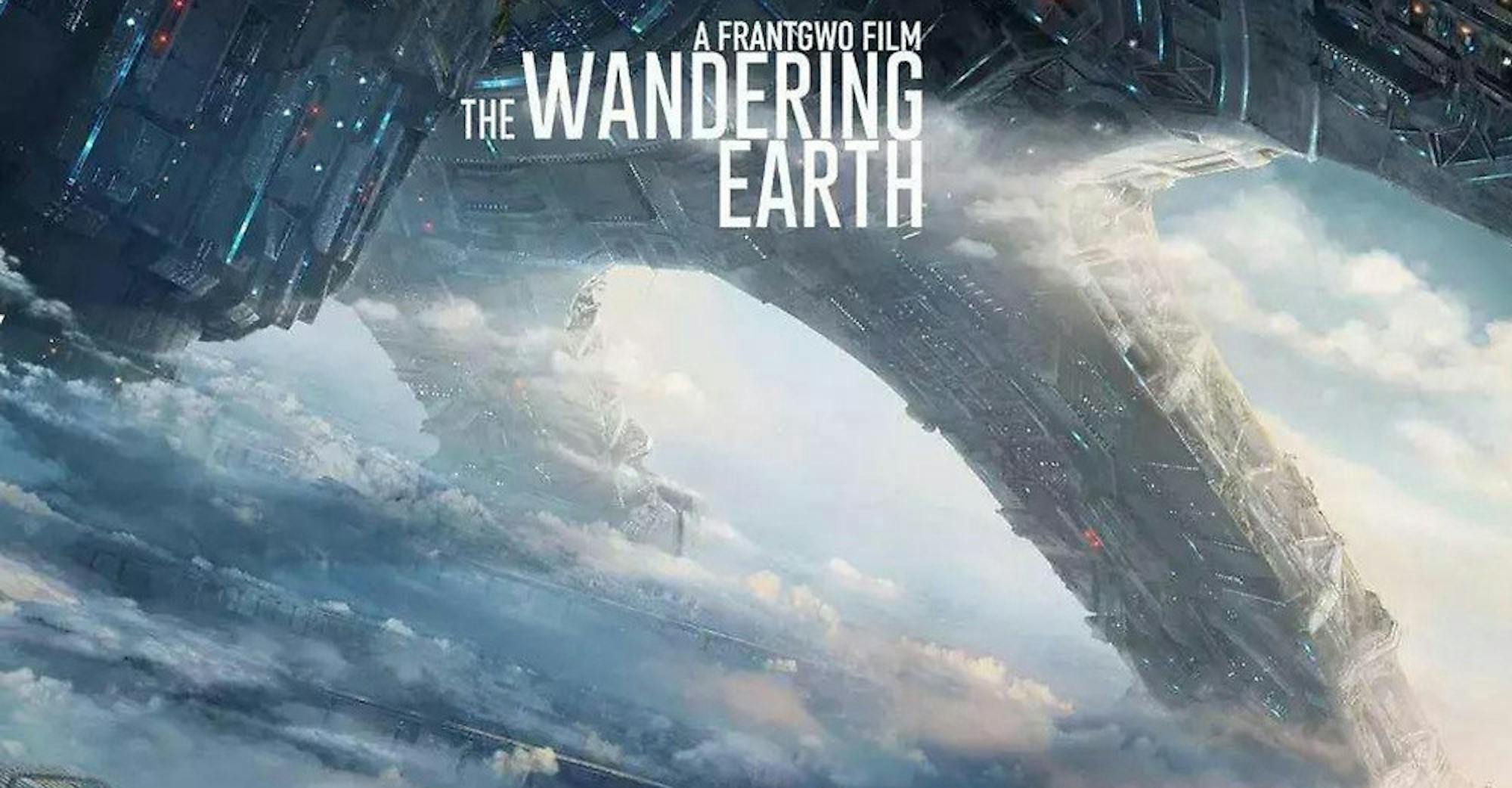

A promotional image for 'Wandering Earth' (2019) is shown.

Summary

"The Wandering Earth" pays tribute to Western sci-fi films while embodying uniquely Chinese characteristics.

4.5 Stars