A copy of Austrian director H. K. Breslauer's 1924 satirical film "The City Without Jews," presumed lost for decades, was discovered in 2015 at a Paris flea market in astonishingly good condition. The film, based on Hugo Bettauer's 1922 novel of the same name, became the subject of a crowdfunded restoration campaign led by the Austrian Film Archive. Since its re-release, "The City Without Jews" has been touring the festival circuit, which brought it to Brookline's Coolidge Corner Theatre earlier this month as part of the Boston Jewish Film Festival, screened with live musical accompaniment by Jeff Rapsis.

The film, which took great influence from the Austrian political climate of the time, opens as the Austrian metropolis of Utopia has been caught in a crippling financial crisis. Crowds of jobseekers angrily march through the city's streets, blaming the city's Jewish population and demanding their banishment. A majority of the city council is only too happy to indulge their own antisemitism, and an ordinance ordering the Jews to leave in a matter of days is passed. Soon after the Jews are exiled, however, the city's situation worsens: The city's banks fail, the economy collapses even further and a steep cultural decline follows. The citizens soon begin demonstrations demanding a repeal, while a city councilor's daughter (Anny Milety) and her Jewish fiancé (Johannes Riemann), who has snuck back into the city in disguise, must conspire to swing the vote in their favor.

"The City Without Jews" is an early example of film that addresses the sudden departure of an entire demographic, but it is not the only example. In Sergio Arau's 2004 mockumentary "A Day Without a Mexican," California wakes up one morning to find an eerie, impenetrable pink fog surrounding the state's borders, and all of its nearly 15 million residents of Mexican and other Latinx descent vanished without a trace, sans reporter Lila Rodriguez (portrayed by Arau's wife, Yareli Arizmendi). As in "The City Without Jews," the loss of the state's Latinx population predictably throws Californian society into disarray. The film's poster mockingly displays a frazzled upper-class white couple, rife with sweat and dirt, forced to do their own house cleaning and gardening. The joke is low-hanging, and the film sadly does not make the most of its intriguing premise, but like all good satire, it has a solid truth underlying it. Indeed, the loss of California's Latinx population, despite some incendiary politicians' rhetoric, would be just as catastrophic in real life as it is in Arau's often ham-fisted feature. A CNN editorial discussing the film notes that even absent the economy's dependence on immigrants, the loss of their often-questioned tax revenue alone would cripple the state.

"A Day Without a Mexican" failed to make much of a commercial or critical impact in its day, and the circumstances surrounding this film are vastly different from those surrounding the making of "A City Without Jews." Yet the parallels are eerie: "The City Without Jews" was released in July 1924, 14 years before Austria's 1938 Anschluss, or annexation, by Nazi Germany. "A Day Without a Mexican" was released in May 2004; 14 years and three presidents later, hate crimes targeted at Latinx individuals rose by 15 percent from 2015 -- when Donald Trump announced his candidacy -- to 2016, and images of migrant children tear gassed at the border have gone viral in recent days, sparking international outcry. Antisemitic hate crimes have also risen -- last month's mass shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh became the deadliest act of antisemitic terror in American history.

Today's seemingly rapid backslide in social progress has many in the cultural world looking back to the era of "The City Without Jews" with unease. Those dumbstruck by what is happening need only rewind to the 1920s in central Europe to get a clue. During the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Jewish citizens, driven by the liberalization of laws restricting their movement, the economic opportunities of industrialization and later by conflicts like World War I, began migrating in large numbers from villages in the empire's eastern regions to its prosperous cities, Budapest and Vienna. By 1920, there were over 200,000 Jews living in Vienna, a figure representing nearly one in nine people in the city. The Jews of pre-Nazi Vienna formed a prosperous and integral part of the Austrian capital's society, ranging from business magnates to writers like Stefan Zweig to famed psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Jewish socialites such as Adele Bloch-Bauer, immortalized in the paintings of Gustav Klimt, were prominent players in the city's cultural landscape. Certain districts of Vienna had Jewish majorities, and many more were over a third Jewish.

Despite these advancements, however, Jews in Austria remained vulnerable. Around the turn of the 20th century, the Christian Social Party gained a considerable amount of traction running on an Austrian nationalist platform, with much antisemitic and white supremacist influence. Karl Lueger, one of the party's founders, served as mayor of Vienna from 1897–1910. Lueger was a self-proclaimed admirer of Edouard Drumont, founder of the Antisemitic League of France. Adolf Hitler, who lived in Vienna for a portion of Lueger's mayoralty, cited Lueger as a political influence. Later Christian Social Party figures, like Ignaz Seipel, who served two stints as the Chancellor of Austria during the 1920s, served as direct inspiration for characters in "The City Without Jews."

"The City Without Jews" ends on an optimistic note though, as the German populace come to their collective senses, democracy wins out and Jews are welcomed back into the city with open arms. Even viewers with only the most cursory knowledge of history could note that life, unfortunately, did not imitate art.Following the Nazi Party's rise to power in Germany in 1933, similar tensions that had been boiling between political forces on the left and right in Austria throughout the 1920s finally erupted into a brief civil war in 1934.

The result was the establishment of the fascist Federal State of Austria, led by the Fatherland Front, created by a merger of right-wing parties. Jews, increasingly targeted by legal persecution and harassment under the Austrofascist regime, began emigrating in droves. When the Nazis marched into Vienna in March 1938, nearly 40,000 Jews had already left the city. Jews and other minorities were subsequently barred from voting in the Anschluss referendum, in which over 99 percent of Austria's German population voted for annexation into Nazi Germany. Deportations of prominent Jews began in 1939. By the war's end, fewer than 3,000 Jews remained in Austria.

Even the original novel's author did not escape the rising tide of right-wing nationalism — Bettauer (who was not Jewish) was murdered by an Austrian Nazi just months after the film's release. Over 90 years after its release, the film's prescience and unlikely discovery have opened up a window into the fragile halcyon of Jewish cultural life before fascism obliterated it. Only time will tell if "The City Without Jews" will become part of the wake-up call that it once failed to be.

'The City Without Jews' shines unsettling spotlight on history of antisemitism

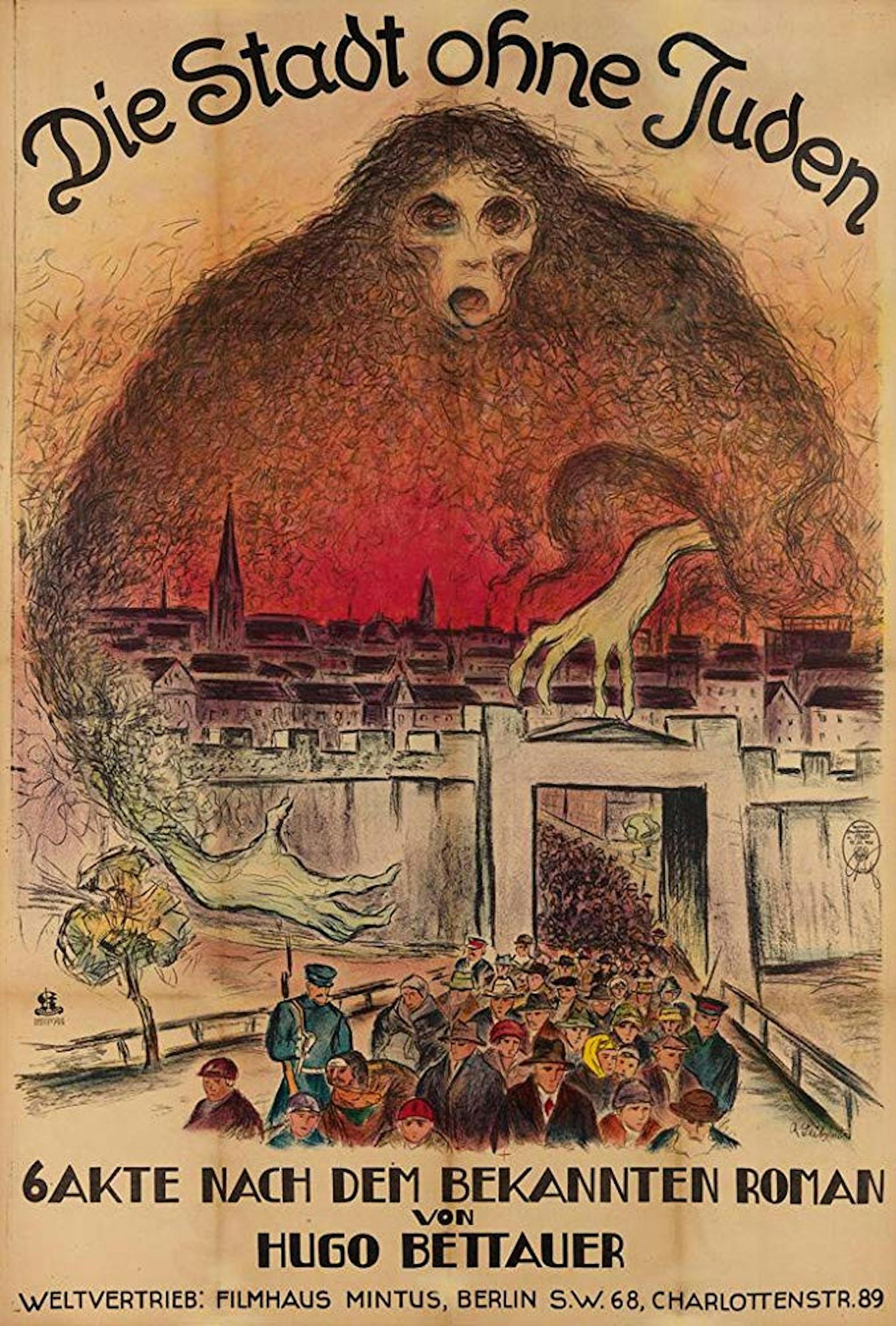

A promotional poster for the movie 'The City Without Jews' (1924) is pictured.