Content warning: This article discusses violence.

"The Hate U Give," a cinematic adaptation of Angie Thomas' bestselling novel of the same name, graphically addresses the Black Lives Matter movement through the eyes of a young black woman, Starr Carter (Amandla Stenberg). A code-switching chameleon of self-expression jumping between diametric worlds, her life in Garden Heights is saturated with warm tones, the familiarity of neighborhood and dilapidated buildings with priceless sentimental value. Starr’s home life visually and emotionally contrasts with the blue-toned, uniform-clad, rich, white-dominated world of her private high school, where she tempers her speech and mannerisms to steer clear of stereotypes despite the blatant appropriations that surround her.

The two versions of Starr collide when she witnesses the shooting of her friend Khalil (Algee Smith) by a white police officer and must decide whether or not to testify, putting herself and her family at risk. She must also contend with the vitriol of an All Lives Matter mentality expressed by her white friend Hailey (Sabrina Carpenter).

The real tragedy of the story is not the violence and trauma itself, but the predictability of the narrative. The circumstances of Khalil’s murder are all-too familiar: Unarmed black man is killed by a white police officer, and the legal system fails to deliver due justice. "The Hate U Give" may be young adult fiction, but it speaks painfully to today’s lived reality for black Americans.

The film establishes a determined, somber tone in its first moments, when ten-year-old Starr and her younger siblings receive “the talk” from her father Maverick (Russell Hornsby) about police encounters and the tenets of the Black Panther Party platform. Reactions to this scene throughout the movie theater reflect the diversity of who is watching it. The normalcy of such conversations within black families may come across as tragic and bewildering to some or painfully familiar to others. "The Hate U Give" has the capacity to resonate as an exercise in empathy and prolonged discomfort, depicting the trauma that Starr and the Garden Heights community experience time and time again. To many, however, these images echo a reality that does not end once the credits roll. The extent to which this film succeeds in portraying their experiences is beyond this reviewer's capacity to determine (it would be inaccurate and irresponsible not to acknowledge how race has influenced this reviewer's perspective as a non-black person), but it certainly creates a more visceral cinematic experience for better or worse.

An additional lens into race relations stems from a real-life source: Tupac Shakur. The rapper's concept of “THUG LIFE” inspired the book’s title and is featured prominently throughout the film. Shakur, who often combined his hip-hop with activism, said that "THUG LIFE" stands for “The Hate U Give Little Infants F***s Everybody,” a mentality that Khalil especially takes to heart. Sprinkled throughout the narrative are moments where the internalized anger and fear on the part of black communities give way to damaging situations. Starr’s uncle Carlos (Common), a black police officer, navigates his internalized racism; a peaceful “Justice for Khalil” protest escalates to a violent riot. Starr’s little brother Sekani (TJ Wright) grapples with grief, language and trauma through the impressionable mind of a child, culminating in a distinct moment at the film’s end that changes his entire family.

As Thomas and director George Tillman Jr. suggest, the hate given to the young perpetuates a cycle that only hurts everyone in the end. However, placing the onus of fixing racial violence on black Americans is quite a jarring conclusion to arrive at after two hours of violence and systemic injustice at the hands of mostly white characters. Perhaps this is meant as a departure from the typical Black Lives Matter narrative, positioning "The Hate U Give" as a movie separate from, but still in conversation with, more traditional narratives of racial injustice and white privilege in American society and how to dismantle it.

Structurally, "The Hate U Give" does not quite know how to exist in a cinematic form. The film’s flaws rest not in its narrative, but in its unsuccessful adaptation. Screenwriter Audrey Wells refuses to trust the emotionally evocative and politically charged images to tell the story, and overcompensates by adding voice-overs which feel redundant and forced. In terms of genre, the film is not a study of Starr’s aforementioned worlds, nor a coming-of-age or family drama — though the scenes between Starr and her family present a refreshingly nuanced portrayal of an African-American family. It is not quite a media or legal circus either, only leaning into those elements when the pacing starts to drag. These tropes surface from time to time throughout the film, albeit in a sprawling manner, culminating in an extended run time of over two hours. There is no easy or right way to convey the scope of such a complex topic within the length of a feature film (which might explain a recent trend toward television adaptations), but that is part of the challenge and the art of the process that this version of the story could not quite manage.

However, there is one way in which this story successfully translates to film. Starr is not the only one implicated as a witness to racial violence; the audience is as well. Tillman’s direction places the camera in Khalil’s car at the time of his death. It seats the audience at the Carter family table. It forces viewers to follow Starr through the bleach-white hallways of her high school, as she dodges microaggressions and modifies herself to assuage the prejudice of her peers. It drops the audience into the heat of a Black Lives Matter protest and eliminates the escape valve of a remote control. Like Starr, we alone have the ability to take action. It is our choice whether we speak up or stay silent.

'The Hate U Give' reflects realities of racial violence through a young woman's perspective

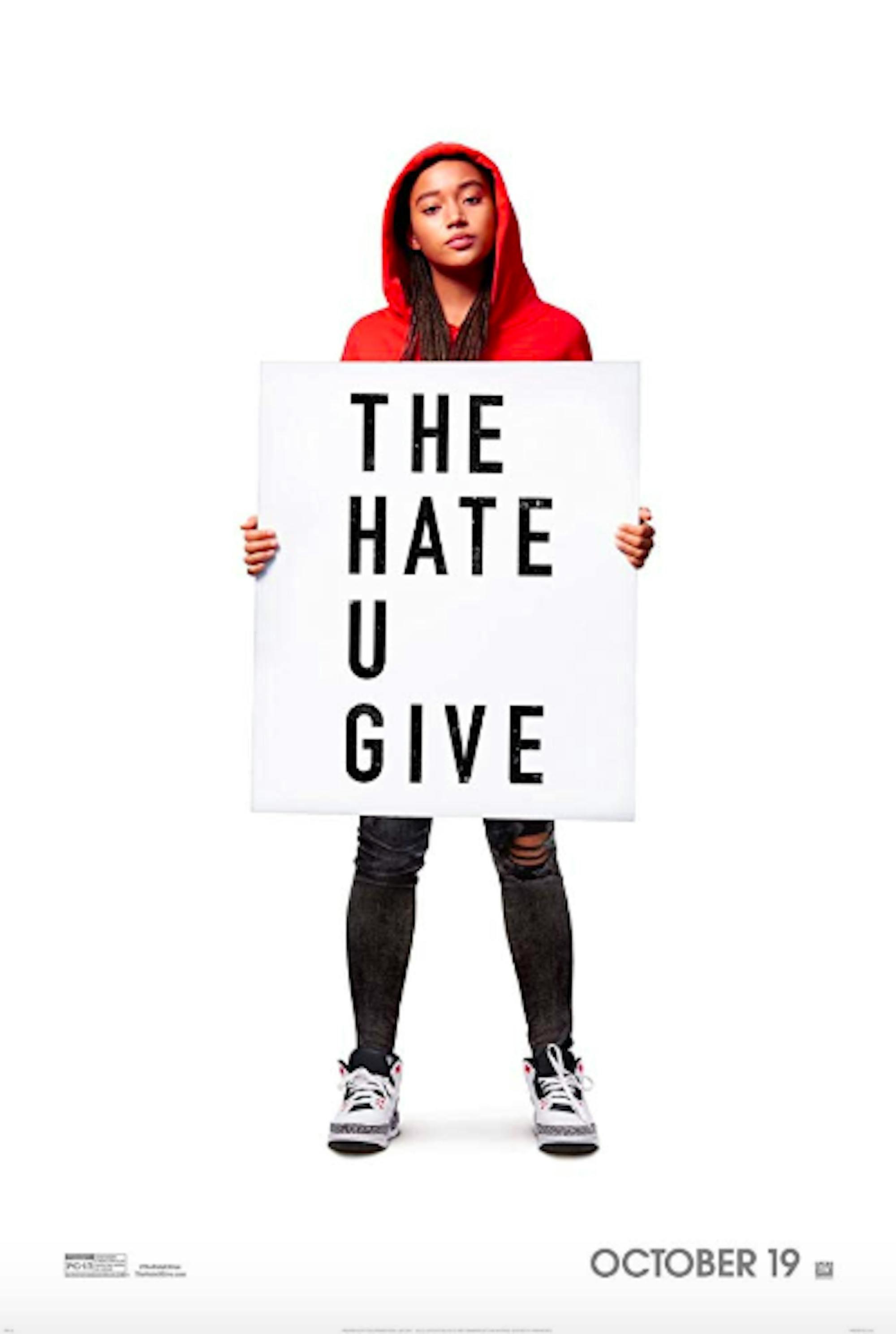

A promotional poster for 'The Hate U Give' is pictured.

Summary

"The Hate U Give" struggles to find its footing in its cinematic form, but its unflinching depictions of racial violence defiantly challenge viewers to stop keeping silent.

3.5 Stars