"There you are," the blurry, zoomed-in face of a nurse says to the audience in the first image of the "Madeline's Madeline" (2018). Is she speaking to us the viewers, to a baby being born or to a patient rising from sleep? "What you are experiencing is just a metaphor," the nurse seems to reassure. But metaphor through art, the lead character and movie's namesake realizes, provides little comfort or clarity at all.

Madeline, played by Helena Howard, is a biracial teenager in an adult theater company with rehearsals that seem to include acting, improvisation and interpretive dance. As company director Evangeline (Molly Parker) quickly realizes, Madeline acts with talent and depth far beyond her years. With quiet intensity, Madeline wins Evangeline's heart and becomes her unintentional protégé while raging outside of class against her overbearing, infuriating mother Regina (Miranda July). As Madeline begins to open up to Evangeline about life outside of rehearsals, Evangeline becomes more and more enamored with Madeline's experience and makes it the focal point of her new production. Eventually the art becomes too real; the project becomes all about Madeline and her relationship with her mother and tumultuous internal psyche, in a surrealist, bildungsroman tale of art and personhood. Who owns a story? Does art retell, enhance or distort reality? When did growing up become about everyone else? It is "Barton Fink" (1991) meeting Greta Gerwig.

Beside the fact that "Madeline's Madeline" is a movie about acting — the very concept of becoming something else — the film consistently manages to distort reality in new, visceral ways. The cinematography and audiovisual effects are experimental and immersive. Voices speak simultaneously and head-rush is conveyed with light filters and warping. As the audience gets some clues into Madeline's troubled life through references to medications and a mental hospital, she becomes an unreliable narrator. This is when the movie gets good. But as Madeline's tension mounts, so does the plot. When Evangeline takes a rehearsal too far, Madeline realizes her own power through art and how she can use it to bite back. This is when the movie gets great.

Much of "Madeline's Madeline" centers on femininity and the struggle to realize one's own womanhood, and writer/director Josephine Decker does well to play with conventional feminine tropes. For example, pregnant women in movies are often carriers for the ambitions of the father — like Satan trying to conquer the earth in "Rosemary's Baby" (1968), or the artist willing to let his fanbase consume his creation in Darren Aronofsky's "mother!" (2017) — and similarly, Evangeline is pregnant and embodies the literal and artistic creator. The name "Evangeline," like the titular "Rosemary," carries divine or Christian connotations, as lofty as her character's artistic vision. Regina, which means "queen," is overbearing in a tyrannical but grounded way. Madeline is caught in between, struggling to assert her personhood to her mother while protecting it from the prying eyes of her director, who is uncomfortably eager to hear about Madeline's dreams of people in pigs' heads and burning her mother with an iron. But Madeline also understands that identity of any sort can be a burden; her room is disconcertingly covered with pictures of girls with their faces cut out.

Other movies have explored how art — particularly acting — affects the artist and blurs the line between fantasy and reality, including "Black Swan" (2010) and "Birdman" (2014). But few have considered the perspective of the subject of the art or the autonomy of the art itself. In fact, "Madeline's Madeline" is more reminiscent of David Lynch's "Mulholland Drive" (2001) both in its dreamlike imagery, as noted by other reviewers, and themes of theater's potential perversity and distortion. Howard, like "Mulholland Drive" star Naomi Watts, is a real-life newcomer actress playing a newcomer actress who finds herself manipulated and confused by those around her. In both movies there is acting of 'acting,' and both performances are masterful. If the scene-within-a-scene catapulted Watts to stardom, Howard's deserves even greater acclaim; no one else has even touched Watts' performance until now.

It would also be a mistake to gloss over the racial element of the story. Although Madeline is biracial, her mother is white, and Madeline is also one of the very few people of color in the company. In an early moment in the film, Evangeline brings in an ex-prisoner, who is black, to share his story to her students, using it as inspiration for the students' own interpretive skits or dances. When another white student mentions using prison as a metaphor, we see directly how artistic interpretation turns a social reality into something conceptual and relatable, but lacking its palpable, original significance, particularly to those marginalized communities it affected in the first place. Madeline's story is personal, but it also speaks to how minority voices can be appropriated and even capitalized on by white artists for the sake of "metaphor."

"Madeline's Madeline" is running through Sept. 24 at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge.

'Madeline's Madeline' blends metaphor, reality through one girl's eyes

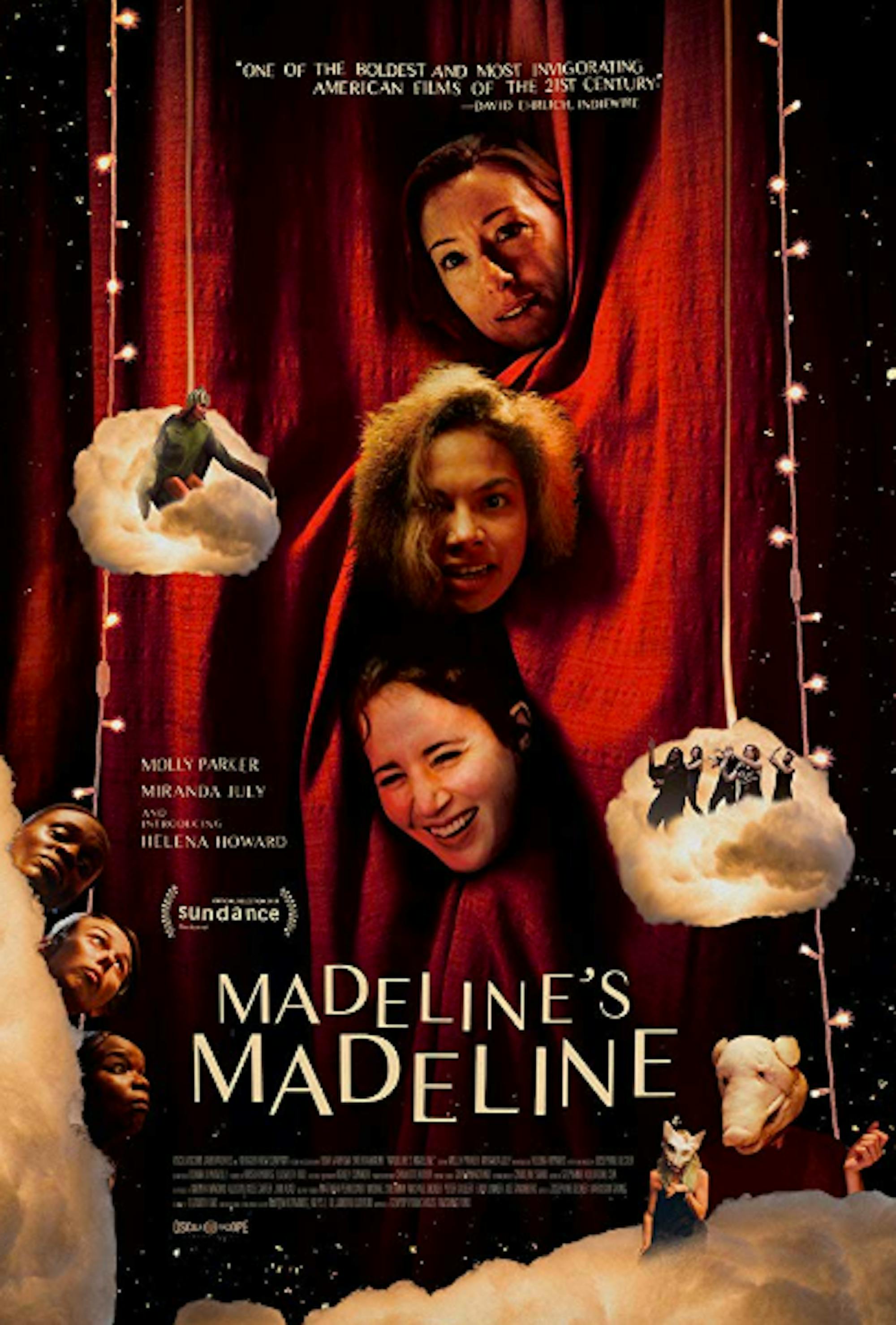

A promotional poster for thriller "Madeleine's Madeleine" is pictured.

Summary

"Madeline's Madeline" is a surreal, intimate exploration of art and the individual.

4.5 Stars