"The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel," begins William Gibson’s seminal dystopic science-fiction novel “Neuromancer” (1984). Set around 2035, the novel imagines a grimy, “cyber-punk” future where hyper-advanced technology has done nothing to rectify social ills and where protagonists lead lives filled with drugs, cybercrime and all-too-real violence.

Netflix’s new series “Altered Carbon," based on the Richard K. Morgan novel of the same name, is cast in the image of “Neuromancer." But where “Neuromancer” dwells on the implications of global computer networks and artificial intelligence, “Altered Carbon” concerns itself with immortality. In the universe of “Altered Carbon," reverse-engineered alien technology allows the human mind to be stored on a small disk, called a “stack," implanted at the base of the neck. Should a person’s physical body die, they can be placed into a new body if their “stack” is intact. As most everyone has a stack, all of humanity is theoretically immortal — catastrophic neck injuries non-withstanding. In practice, however, only the members of an outrageously wealthy social elite, dubbed “Meths” after the long-lived biblical figure Methuselah, have the resources to achieve something approaching immortality. The series follows Takeshi Kovacs (Joel Kinnaman/Will Yun Lee), a long-dead terrorist, who is resurrected by a Meth, Laurens Bancroft (James Purefoy), to investigate an attempt on the latter’s life.

The idea that human consciousness could be shorn from the physical body is a fascinating idea, which, like any good science-fiction premise, raises endless questions. How do notions of race, gender and age work in a world where people can reasonably expect to inhabit widely different bodies during their lifetimes? What are the societal implications of an immortal social elite? What role does religion play in a universe where humanity has effectively conquered death?

“Altered Carbon” is certainly cognizant of all these issues but addresses each of them clumsily. The idea of an identity divorced from any physical characteristic is barely explored, and the religious implications of immortality are given scant consideration. Catholics refuse to be resurrected in new bodies after death, but the idea is only really considered in the context of murder investigations, where an investigator’s inability to resurrect and interview a Catholic victim is presented as a major inconvenience. “Altered Carbon” does meditate on the implications of an immortal social elite, but the show’s ham-handed meditations on the matter are far from thought-provoking. Meths, for instance, live in mansions lofted above the clouds on enormous skyscrapers in a painfully obvious allusion to their effective divinity.

Kinnaman delivers a mostly wooden performance as main character Takeshi Kovacs. Kovacs, a centuries-old former terrorist, is an almost comically cynical, hard-boiled protagonist who regularly spouts drivel about the nature of death and pain. But what Kovacs lacks in fully realized dialogue, he makes up for in his capacity for violence. The character is a regular participant in magnificently choreographed fight scenes, where Kinnaman’s imposing frame and perpetual frown are an asset.

Kinnaman’s performance as Kovacs illustrates the problems with “Altered Carbon” in miniature. Kinnaman delivers his poorly written lines unconvincingly but brings an impressive physicality to his many, many fight scenes. And just as Kinnaman is able to redeem his weak performance with excellent fight scenes, “Altered Carbon” somewhat recovers from its bungling of the weightier themes by falling back on sex, violence and visual splendor.

Ultimately, “Altered Carbon” comes across as a poor man’s “Westworld” (2016–). Netflix clearly spent lavishly on the show’s production, sparing no expense where visual effects, props and fight choreography are concerned, but “Altered Carbon’s” writing does not live up to its production values. Science-fiction fans might appreciate the visually well-realized setting, but general audiences will find nothing more than a sex- and violence-filled romp set in the future.

Netflix's 'Altered Carbon' collapses under brilliance of its premise

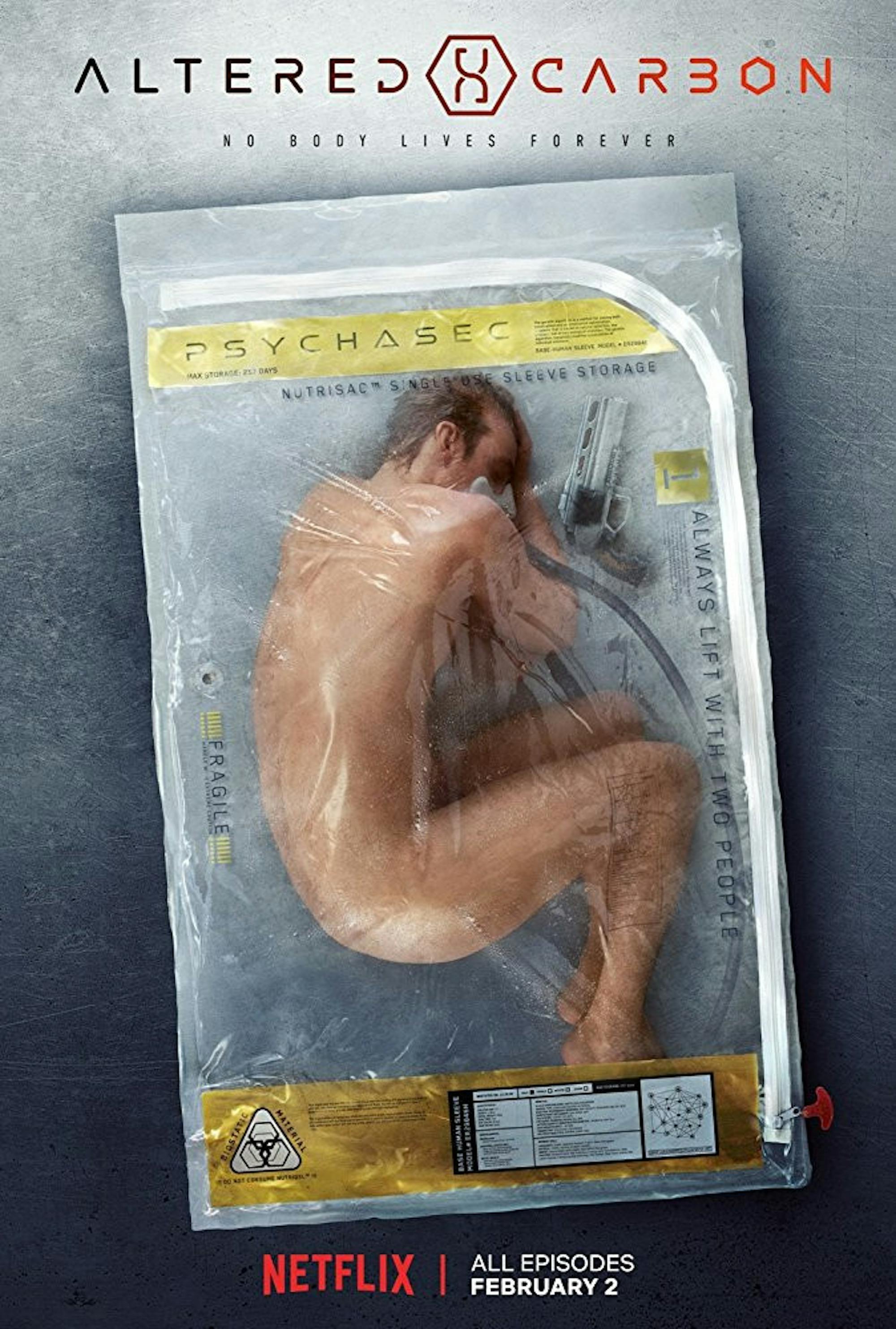

Joel Kinnaman appears in a promotional poster for 'Altered Carbon' (2018).

Summary

Though visually impressive, "Altered Carbon's" writing is too weak to justify watching its 10 episodes. Skip this one.

2 Stars