A glass display case is built into the wall separating the varsity weight room from the practice basketball court. Within it reside the spoils of past battles. This Friday, a football will turn 100 years old. It is on eternal exhibition with white letters carefully painted on: “Textile Field – Tufts 27 – Dartmouth 0 – Nov. 17 1917.”

A century later, the story of the greatest win in the history of Tufts football is one worth recounting and remembering. Fully appreciating that resounding victory, however, requires delving into the historical context in which the game was played.

In the final years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, football experienced both rapid growth in popularity and frequent changes to its rules. Then, as now, the sport’s violence spurred its burgeoning popularity and its eventual reform.

The game literally killed its players. One recent analysis by the Washington Post found that “in 1905 alone, at least 18 people died” playing football. That December, amid growing public concerns about the number of casualties associated with the sport, President Theodore Roosevelt called for a White House meeting with the leaders of the game. Attendees included the leading athletic officials from the period’s football powerhouses, notably Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

According to Michael Weinreb, author of "Season of Saturdays: A History of College Football in 14 Games" (2014), Roosevelt did not impose changes from on high. Rather, the 26th president’s greatest contribution was bringing the leading figures of the sport together and asking them important questions about the game’s past, present and future.

“He was kind of the facilitator more than anything else,” Weinreb said in an interview with the Daily. “There was so much criticism and so much attention on guys dying on the field.”

The new committee made a number of rule changes for the 1906 season, including one that completely revolutionized the sport: the legalization of the forward pass.Mark F. Bernstein, author of "Football: The Ivy League Origins of an American Obsession" (2001), described the safety-minded intentions behind the rule change.

“[Beforehand,] everything was massed into a very tight, on-the-line kind of play,” he said. “The forward pass was introduced as a way to open up the game [and] spread people out.”

Weinreb explained that Notre Dame’s 35–13 victory over the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (Army) in 1913 helped overcome some Eastern schools’ reticence to use the forward pass.

“[They] either felt like it was a gimmick or like it didn’t really add anything to the sport,” he said. “[The Notre Dame–Army game] helped popularize it in the East and made it a bigger thing.”

Still, in 1917, passing was far less commonly used than it is today, in part because of the size of the equipment. Bernstein noted that the football would not be reduced to its current dimensions until the 1930s.

“[In 1917, the ball] would’ve been noticeably bigger and thus harder for guys to get a grip on and throw,” he said. “My sense is that [passing] was used maybe four or five times a game.”

Kent Stephens, historian and curator of the College Football Hall of Fame, cited a similar explanation for passing’s secondary tactical status at the time.

“The ball itself was three inches thicker around than it is today, and it wasn’t streamlined like it is today,” he said. “Passing really was not a big part of offense.”

The legalization and gradual proliferation of the forward pass provided college football with the opportunity to become one of the most popular sports in the country.

David Shribman is the executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, a Pulitzer Prize-winning political reporter, and — perhaps most importantly — a 1976 Dartmouth graduate. He also co-authored a book about Dartmouth football titled "Dartmouth College Football: Green Fields of Autumn" (2004). He explained that, in 1917, while the game was not yet at the level of popularity it would later achieve, it was well on its way.

“Not in 1917, but for sure 15 years later, college football was a nationwide mania,” he said. “College football wasn’t as big as baseball, but it was getting very, very big indeed, and the Eastern schools were preeminent.”

Stephens cited several advances in technology — including radio, moving pictures, and improved roads and automobiles — that facilitated college football’s rise to prominence.

“I don’t think it really became a true national game until the maybe early 1920s,” he said. “Before, if you wanted to get large crowds of people together, you could only do that in urban areas. [By the 1920s,] major universities in more rural areas were able to draw people [to their games].”

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the schools that would eventually constitute the Ivy League dominated the game of football.

“The Ivy League was where football grew in those early decades,” Weinreb said. “Football just became part of the Ivy League’s identity … It was something that the Ivies did better than anybody else.”

Meanwhile, smaller institutions like Tufts — though of a similar academic caliber — paled in comparison to Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Penn and Dartmouth when it came to athletics.

“Schools like Tufts and Williams were always kind of small time,” Bernstein said. “They played Yale and Harvard in those early years a lot, but they were the early season games. [The Ivy League schools] would run up the score on them and just practice to get in shape.”

Shribman confirmed Tufts’ second-class status as a football program.

“Tufts was not a huge power in college football,” he said. “Places like Dartmouth and Harvard would play schools like Norwich and Tufts to fill out their schedules.”

In 1917, the game of football looked significantly different than it does now. While leather helmets — called “leatherheads” — were permitted (though not required), a 1913 official rulebook stated that “if head protectors are worn, no sole leather, papier-mâché, or other hard or unyielding substance shall be used in their construction.” In other words, the solid plastic exteriors of today’s helmets would have been illegal a century ago.

Stephens described other features of football equipment, now taken for granted, that had not been invented yet. The uniforms were uncomfortable and heavy, he noted, and cantilevered padding — which disperses the force of a hit, thereby lessening the impact and risk of injury — had not yet been developed.

“The cleats were made out of wood and leather. They didn’t use any kind of synthetic material such as plastic,” Stephens said. “The uniforms were certainly real thick and made out of wool … and the pants were made out of canvas.”

Meanwhile, the teams used formations like the T-formation and the single wing that, though they seem antiquated now, transformed the way the game was played. Passing was employed infrequently, while “mass momentum” plays — which Weinreb described as “a flying wedge of players [that would] just run over people" — were still in use, albeit declining.

The players were smaller, too, as they lacked access to 21st-century knowledge about subjects like training and nutrition. Given what are, by modern standards, extremely stringent restrictions on substitutions, teams employed “one-platoon systems” – simply put, participants played on both offense and defense, rather than specializing in one or the other.

Thus, in many ways, the game was different in 1917 than it is today. Still, football was football, and with each passing year, the audiences grew.

This is the first part of a two-article series about the 1917 Tufts-Dartmouth football game. The second part will be published on Friday.

History in the huddle

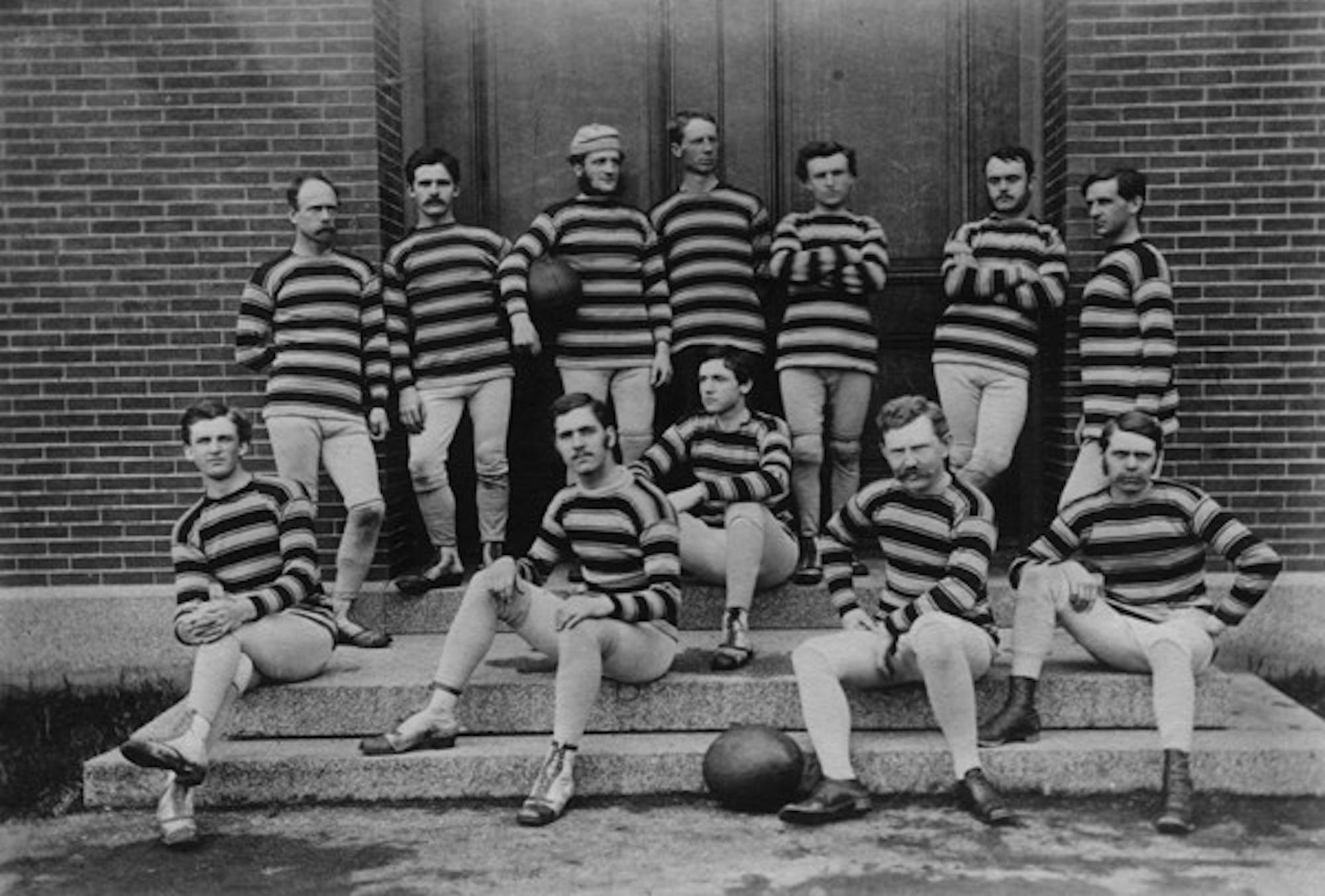

Twelve Tufts football team members pose for a portrait in uniforms in 1876.