“Moonlight," released on Oct. 21, tells a familiar story with unfamiliar characters and uncommon understatement. In what is shaping up to be his breakout picture, writer and director Barry Jenkins has adapted Tarell Alvin McCraney’s never-produced play, “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” and woven in his experience growing up in Liberty City, Miami. The film chronicles the childhood, youth and adulthood of a gay black man, Chiron, played respectively by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders and Trevante Rhodes.

As the centaur Chiron of Greek myth was a contradiction, this Chiron knows also he is different even from a young age. After a tussle with friend Kevin (played as a teenager by Jharrel Jerome), Chiron lies on his back, mouth open in the beginnings of a revelation. Withdrawn and bullied, he is adrift and communicates his plight with a bowed head and cautious eyes. His home is no emotional haven, as the grip of addiction prevents his single mother Paula (Naomie Harris) from being there for him. His only confidants are drug dealer Juan (Mahershala Ali) and Juan’s girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe), who provide for him when Paula cannot.

As Chiron matures into a high schooler, he remains unsure of who he is and who he should be, even as his peers become surer that they should hate him. His bond with Kevin comes to a climax that does not go unpunished, and this chapter ends as Chiron begins to take a stand.

But that stand isn’t for who he truly is; rather, it’s the beginning of a closing-off and armoring of himself with the trappings of masculinity that he observed in Juan. An unexpected call from an adult Kevin (André Holland) cracks his new exterior, and he returns to Miami from his new home in Atlanta in search of closure and reconnection.

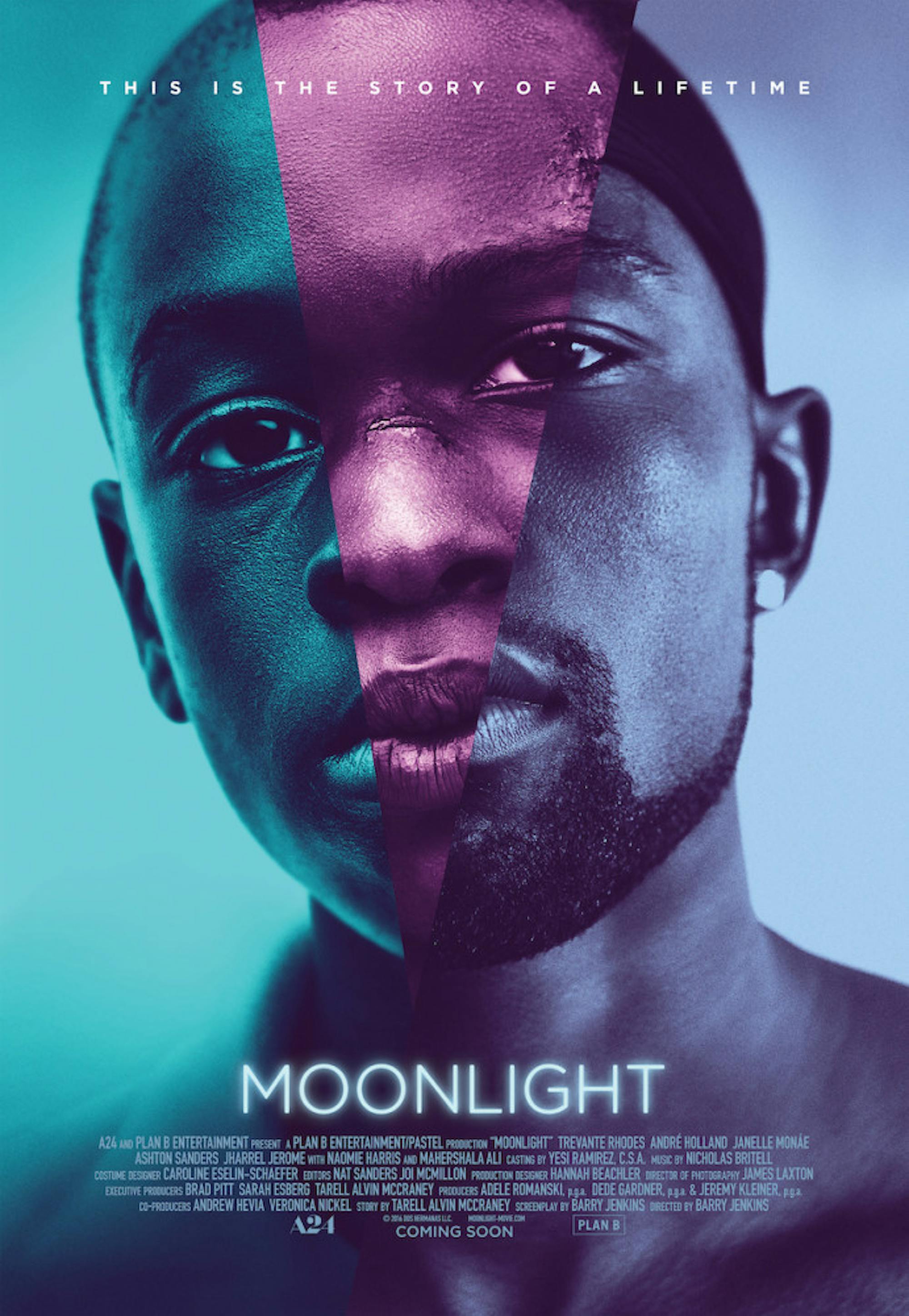

The film is pervaded by a blue-and-red color scheme that gradually blurs as Chiron’s conception of himself matures. The red, it seems, pervades when Chiron or those around him hew to how others define them and actualize stereotypes. His high school tormentor sports a blood-red shirt, and his mother is bathed in red light when she shouts Chiron down before shutting her door on him to turn a trick. But when Juan tells him he must decide who he wants to be and tells Chiron that he “can’t let nobody make that decision for you,” Chiron is centered among a mass of blue: furniture, curtains and the sky.

Cinematographer James Laxton’s camera glides through this dichotomously colored world, circling its subjects and furthering the sense of an unclear future with intermittent out-of-focus shots. When Juan brings Chiron to the ocean to learn to swim, the viewer bobs along with the swells, caught between the air and the water as Chiron struggles to stay afloat.

Though it is captured expertly and effectively, Jenkins’ world, realized by production designer Hannah Beachler, does become oppressive in its insistence on saturating each scene with these themes. There is a self-consciousness to the look of the film that saps it of energy and makes the running time of just under two hours drag in spots as if caught in front of a painting in a museum that is duller than its neighbors.

Aside from that slight stumble, Jenkins has taken great care in putting together the pieces of Chiron’s life, and Jenkins' touch is never heavy. His is the light hand of someone constructing a house of cards, and his assemblage stays standing. But like a deck of cards, all the players are known. The social outcast, the friend torn between loyalty and fitting in, the mentor who is taken too soon. Despite following a beaten path, Jenkins brings the audience closer to his characters than most, and at that distance, where every breath and glance and expression is impossibly rich, there is a realization that the faces on the cards are not what was expected. They're black rather than white, and are breaking archetypes rather than embodying them. By mapping these characters onto a journey one has seen before, Jenkins dismantles conceptions of what they should be. This is a universal story, told about specific people who too rarely bathe in the light of the silver screen.

'Moonlight' uses color, characters to create excellent, carefully crafted portrait

Summary

4 Stars