Throughout her career as a researcher, biology professor Sara Lewis has interacted with members of the scientific community, Tufts graduate and undergraduate students and members of the general public. Though these three groups are separate, one constant has always held true: everyone Lewis has ever talked to about her research, regardless of their understanding of science, loves fireflies.

While Lewis has conducted research using many different species and laboratory subjects, fireflies have proven to be the organism that attracts the most universal interest, as she discovered when doing fieldwork with fireflies in the Great Smoky Mountains many years ago.

“While working in the Smokies, I came across a lot of people out in the woods looking at fireflies,” Lewis said. “They were talking about how God put them on Earth for people to enjoy.”

Many of the people she encountered, she said, did not necessarily believe in biological evolution.

“I realized that one of the opportunities for me as a firefly scientist was to use that enthusiasm people have for this organism as a way to begin to tell them a little bit about the scientific method, and also sneak in a little bit about evolution,” she said. “Fireflies have so many great examples of evolutionary innovations, and of twists and turns in their evolutionary history.”

It was Lewis's personal fascination with fireflies, and her interest in educating the general public about them and about biology more broadly, that led her to devote so much of her biological research to this organism, much of which culminated in her most recent book, Silent Sparks: The Wondrous World of Fireflies (2016). The book covers the most up-to-date scientific discoveries on fireflies using language that is accessible to people outside of the scientific community.

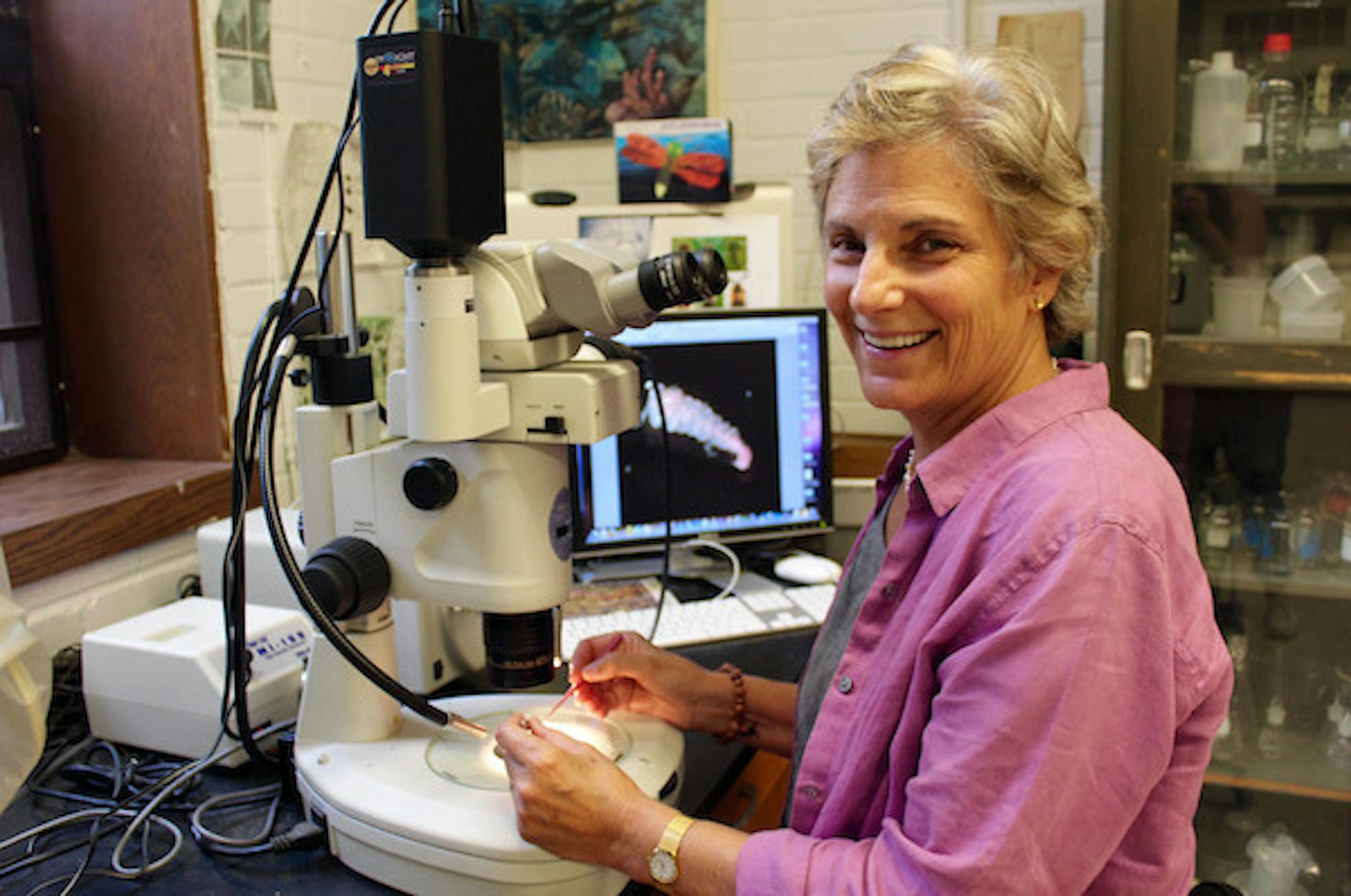

At Tufts, Lewis runs a laboratory that carries out experiments relating to the evolutionary ecology of different kinds of insects, fish and marine invertebrates.She said she is particularly interested in sexual selection,a type of natural selection that has to do with the struggle for reproductive opportunities among members of the same sex, as well as the factors that go into organisms' selection of mates.

She described fireflies as the "perfect" organism for studying the evolutionary process of sexual selection due to their presence in many regions of the world, their universal appeal across cultures and the visibility of their courtship signals and dialogues, which take the form of steady glows and flash signals released by male fireflies.

Additionally, Lewis said the stiff competition between male fireflies makes them particularly fascinating when it comes to sexual selection.

"All the fireflies you see flying around mostly are males," she said. "When I started counting up males and females in the backyard, it was this ridiculously competitive situation: a couple magnitudes more males than females. I thought, 'This is crazy, how do these males figure out how to pass on their genes?'"

Even before she started working at Tufts in 1991, she had long been interested not just in how fireflies select and obtain mates, but in the details of their reproductive process.

"One of the big, outstanding questions that was fascinating to me was, 'What happened after the lights went out?'" Lewis said. "We knew a lot about the courtship of fireflies, but what happened when a male and female finally got together?"

Many of the graduate students who work in Lewis's lab or under her supervision are looking into this question. According to Lewis, two students who just earned their Ph.D.s recently wrote a paper called, "Molecular characterization of firefly nuptial gifts: a multi-omics approach sheds light on postcopulatory sexual selection," which details new findings on the long mating process of fireflies and the contents of the nutrient-rich nuptial gift that is transferred from the male to the female during this process.

"Males and females, once they hook up together, they stay together all night long...[as] males transfer to the females not just sperm and gametes, but a nutrient-rich nuptial gift," Lewis said. "We were able to look at the reproductive tissues in males that produce these gifts and see what proteins they were manufacturing."

Amanda Franklin is a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate working in Lewis' lab. The focus of her research is communication among mantis shrimp, an organism Lewis described as "an interesting beast."

"They fight aggressively for occupancy of little burrows on coral reefs in coral rock," Lewis said. "[Franklin's] interested in the signals they use to communicate with one another about their fighting ability."

Franklin, who hails from Australia, found herself in Lewis's lab after being offered a fellowship to study in the United States. She said she was initially interested in working in a lab that researched sexual selection in marine animals, which led her to Lewis, though Franklin's current focus on mantis shrimp communication and signals still relates to some of Lewis's research.

"[My Ph.D.] project went in a different direction when I started working with the mantis shrimp," Franklin said. "Sexual selection is the main focus of [Lewis's] lab, but she does look into some communication research between fireflies."

Franklin said that working under Lewis's supervision has allowed her to conduct fieldwork in Belize, learn how to use different types of statistical analysis and conduct new types of experiments using various techniques.

"I feel like I've grown as a researcher," Franklin said.

She added that all of her projects involve collaboration between undergraduate and graduate students. This summer, Franklin worked with Michelle Ysrael, a sophomore studying biology and one of Lewis's advisees.

Ysrael said she "shadowed" Franklin, helping with the experimental trials used for her mantis shrimp research. Ysrael is currently taking a year off from Tufts to work for a shark research and conservation organization in Hawaii, and she plans to apply the experience she gains this year to additional biology research when she gets back to Tufts.

"I definitely want to work in [Lewis's] lab when I get back," Ysrael said. "It’s really good to get exposed to the setup early, I think. It’s not like you need the academic background...it’s all about just learning how to navigate a lab. That’s why I started early."

Ysrael said she also looks forward to getting to know Lewis better next year.

"She’s just one of the most passionate people I’ve ever met," Ysrael said. "I’ve never met someone who has so much to say about fireflies."

Lewis spread that passion for fireflies during her sabbatical two years ago. During that time, she worked on research for her book and travelled across the country giving talks about fireflies to anyone who wanted to listen, hoping to bridge the gap between scientific findings and the public's knowledge.

"My research was funded by federal grants supported by taxpayer dollars," she explained. "It seemed to me that I had a responsibility to tell people why we needed these grants."

In addition to giving talks, Lewis led walks in local parks, allowing people to view fireflies and even witness their mating process.

"People had no idea about all of these scientific discoveries," she explained. "The reason for [the lack of knowledge] was that all these results were written up in scientific papers, which are great for scientists to understand, but full of technical jargon. We hadn’t taken the time to translate our results into a form that would be accessible to the general public."

The Lewis Lab: studying sexual selection after dark