You probably heard -- perhaps while trying to stream “1989,” Taylor Swift’s new album, released on Oct. 27 -- that Swift herself removed all her music from Spotify earlier this month. And you were probably pretty bummed that you actually had to (God forbid!) buy the album just to avoid becoming a social pariah. But hey, if Lena Dunham is telling you to buy Swift’s latest creation ... well, you better obey.

“I’m not willing to contribute my life’s work to an experiment that I don’t feel fairly compensates the writers, producers, artists and creators of this music,” Swift told Yahoo about her power play. “And I just don’t agree with perpetuating the perception that music has no value and should be free."

Swift isn’t the first major artist to boycott Spotify. Thom Yorke of Radiohead has been challenging the music industry’s practices for years now, and pulled the Atoms for Peace album, “Amok” (2013), and his solo release, “The Eraser” (2006), from Spotify in 2013 in protest of the company’s business model and mistreatment of new artists.

“The numbers don’t even add up for Spotify yet,” Nigel Godrich, record producer and fellow member of Atoms for Peace, said in 2013. “But it’s not about that … It’s about establishing the model which will be extremely valuable. Meanwhile, small labels and new artists can't even keep their lights on. It's just not right. Plus people are scared to speak up or not take part, as they are told they will lose invaluable exposure if they don't play ball.”

So, how do Spotify's numbers actually add up? And how much do artists actually make on the music streaming service, used by over 50 million people? According to the company, which actually makes its business practices quite transparent, it distributes 70 percent of its revenue back to the “rights holders” of each song: the record label, publisher or the artists themselves.

To determine the “royalty rate per stream,” the company divides the total streams of a single artist’s work in one month by the total number of streams on Spotify in that same month. This creates the artist’s “share,” which is then taken from Spotify’s total monthly revenues, and Spotify keeps 30 percent. So according to the Spotify model, which strongly advocates for a switch to a streaming model for the music industry, the more people that use Spotify overall, the more each artist will make. The wealth, more or less, is shared.

So, when Spotify hits 40 million paid subscribers, an indie album earning $3,300 a month will earn $17,000 in royalties for that same amount of time, information the company recently shared with record labels across the country, according to the New Yorker. And a mainstream top-forty hit, now earning perhaps $425,000 a month, would earn $2.1 million. However, these are merely predictions. Spotify founder and CEO Daniel Ek even admitted there was no way to ensure the accuracy of these predictions. He added, however, "I’m not the only person who believes it. Pretty much everyone is in agreement that streaming will keep on growing over the next few years.”

Taking all the information released by Spotify into account, was Swift’s bold move just a final attempt to fight a machine whose takeover is inevitable? Perhaps. While her album had a solid first week of sales, her sales experienced a 69 percent drop during week two, indicating that quite a few fans waited until they could stream it on YouTube, or maybe steal it from a friend.

And while many argue that Spotify offers a space for new musicians to gain exposure, their payoff per stream really only equates to $0.006 to $0.0084. However, if Ek’s predictions for Spotify prove correct, this "share" ought to increase drastically over the next few years -- leaving Swift's power play in the dust.

“[Swift’s move is] purely P.R.-driven, which is fine,” Richard Jones, the Pixies’ manager, told the New Yorker in the same article. “But let’s not pretend it’s artist-friendly. Because actually the most artist-friendly thing here is for everyone to make streaming into something that is widespread.”

How simple would a transition to a streaming-only model actually be? And how will Spotify fair against other competitors in the game, like Google’s new YouTube Music Key streaming service? Whatever the process may be, one thing seems to be definite: Album sales aren’t going back up any time soon. And whatever chapter comes next for the industry, the change won’t be easy.

“In Sweden, there was one tough year, and then the debate changed,” Ek said. “That will happen in the larger markets. The end goal is to increase the entire pool of music. Anything else is part of the transition ... This is the single biggest shift since the beginning of recorded music, so it’s not surprising that it takes time to educate artists about what this future means.”

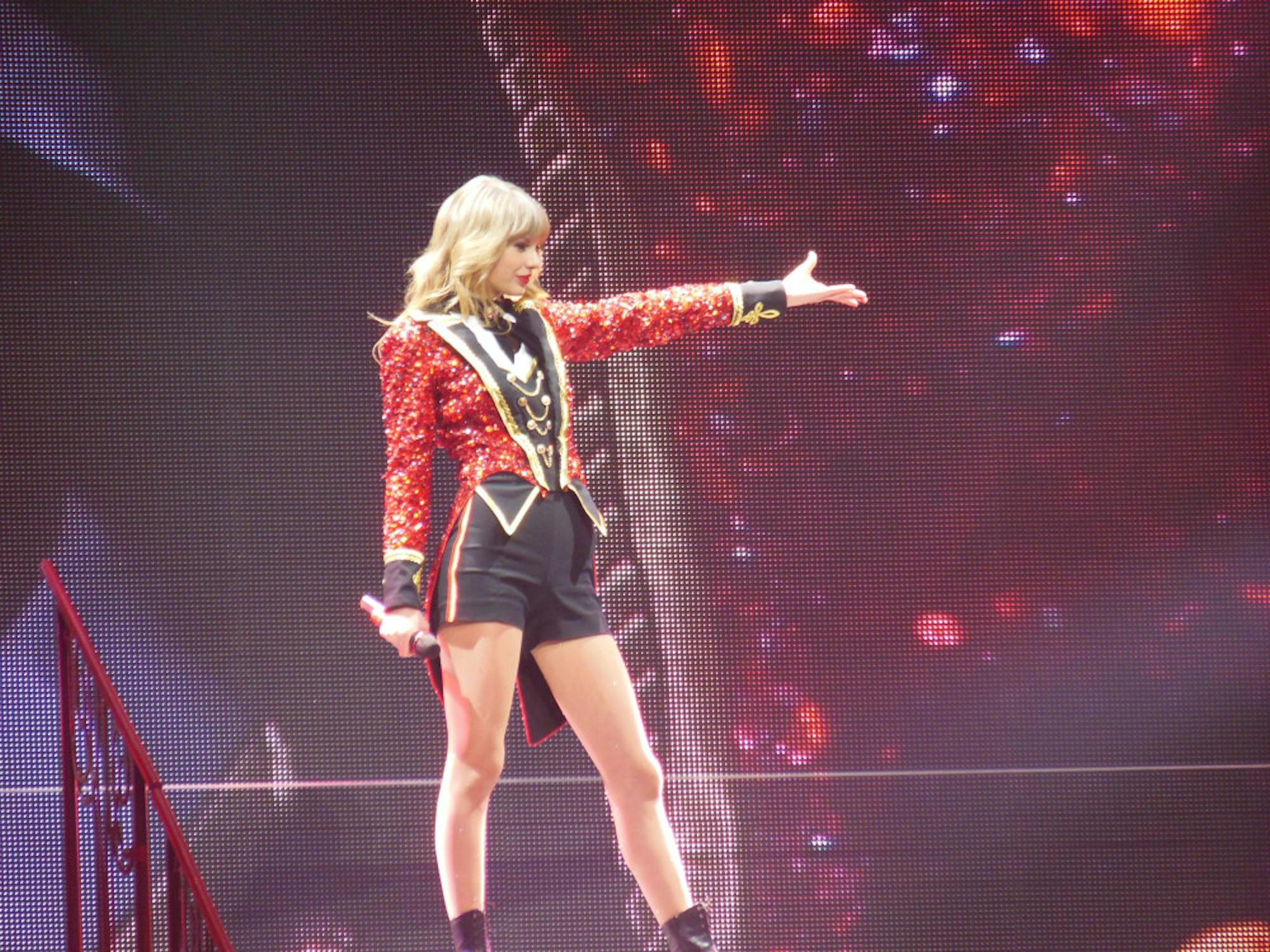

Taylor Swift versus Spotify: is streaming the future?

Pop megastar Taylor Swift recently pulled her new album from Spotify.