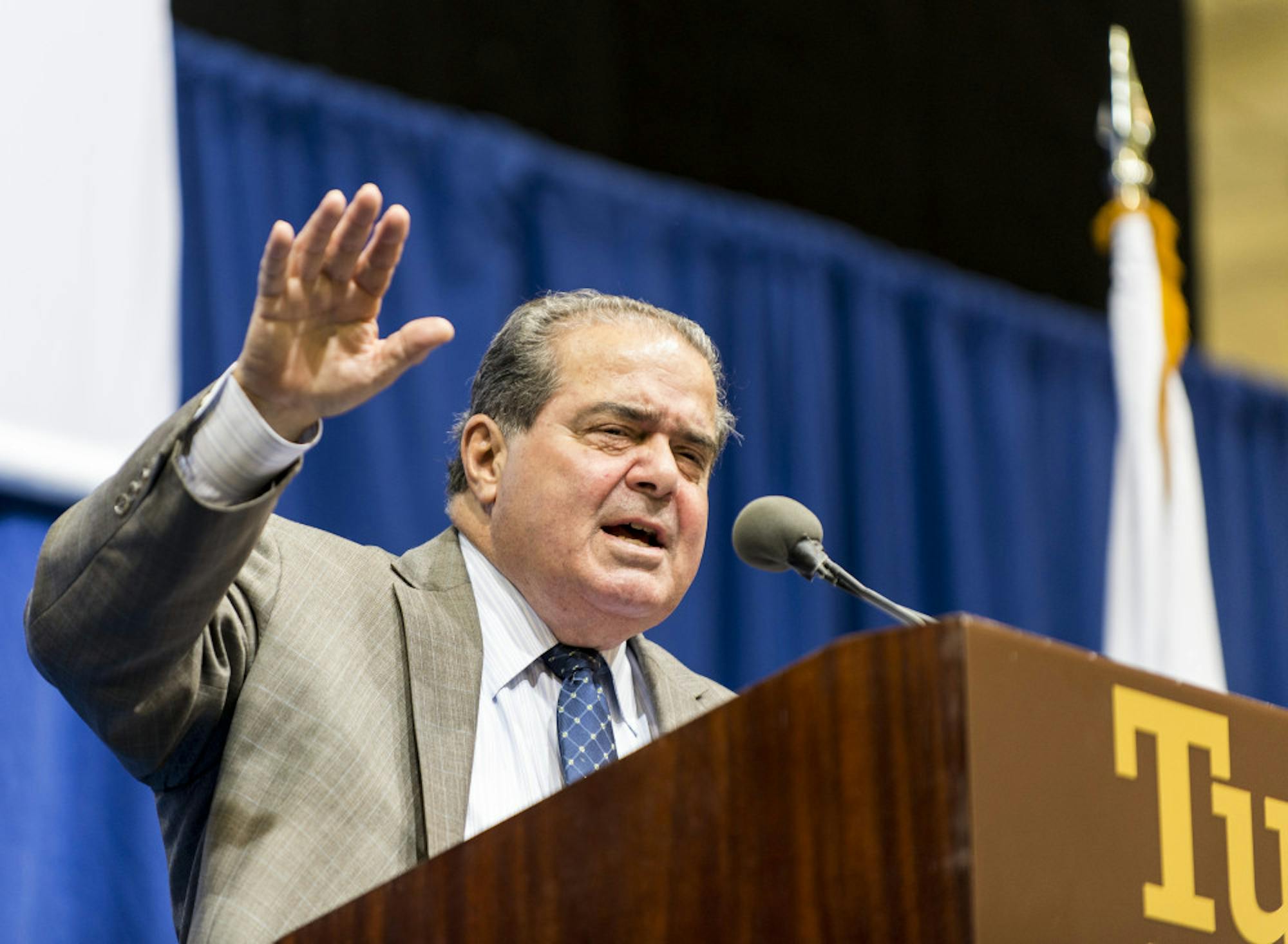

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia delivered the 17th Richard E. Snyder President's Lecture yesterday afternoon at the Gantcher Center.

In his lecture, titled "Interpreting the Constitution," Scalia discussed issues surrounding different doctrines of constitutional interpretation. He began by defining his personal method known as "originalism," a principle of interpretation that tries to determine the original intent of the Constitution's authors.

"The Constitution meant what it meant when it was adopted," he said.

Scalia went on to explain that although originalism was viewed as the "orthodox" interpretation in the past, it is much less popular in the present day. Instead of attempting to interpret the Constitution in light of what its drafters meant to say, modern proponents of a "living Constitution" believe that the document's meaning evolves as society progresses morally, Scalia explained.

Scalia disagreed with the opinion that any societal change necessarily signaled improvement, noting that the founding fathers were wary of possible future moral decay in society while creating the Constitution.

"The Bill of Rights itself is a condemnation of the Pollyanna-ish notion that every day, every way, we get better and better," Scalia said.

Nowadays, Scalia explained, the modern Supreme Court often distorts the Constitution's meaning using the "living Constitution" method of interpretation.

"In the good old days [judges] distorted the Constitution the good old-fashioned way - they lied about it," Scalia said. "With the 'evolving Constitution,' you don't have to lie. You can say, 'Oh yeah, it used to mean that. It just doesn't mean that anymore. Why? Because we don't think so. We don't think it ought to.'"

In an illustration of how an originalist would approach changing the Constitution, Scalia pointed to the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote in 1920. Instead of ruling that the Constitution's restrictions on enfranchisement were unconstitutional by a modern "living" interpretation of the document - as it was previously only men who could vote - an originalist would leave the decision to the will of the people.

"It was understood that you could deny the franchise for a lot of reasons," Scalia said. "Nobody thought that that was unconstitutional. So the practice [of not allowing women to vote] was continued until it was changed ... by Constitutional amendment in 1920. We don't do that anymore."

For the next part of his lecture, Scalia argued in support of his originalist interpretation by listing and then rebutting reasons for adopting the "living Constitution" perspective. He began by exploring the argument that the new method of interpretation provides flexibility.

"If you think that the proponents of the so-called 'living Constitution' want to bring you flexibility, think again," Scalia said.

According to Scalia, his understanding of the Constitution maintained that the states have the power to decide democratically and separately on issues such as installing the death penalty. The "living Constitution" theory, on the other hand, would allow the Supreme Court to decide once and for all on the death penalty debate. In this way, the new method is just as rigid as originalism, except that it ends the discussion, Scalia said.

"If you buy into the 'living Constitution,' and you let the Supreme Court say the death penalty is unconstitutional, that's the end of it," he said. "There's no use debating it anymore. You can't change. Under my system you can go back and forth."

Scalia next discussed if originalism was inherently biased in favor of conservative opinions. He denied this view, arguing that his interpretation of the Constitution was policy neutral. He pointed to two Supreme Court cases - one involving flag burning and the other involving the right of a person to face a witness against him - which resulted in a liberal ruling from an originalist interpretation. While Scalia said he personally believed in a more conservative stance on both issues, he was forced to rule liberally to uphold the original intent of the Constitution writers.

"I confess, I am a conservative," he said. "If it was up to me, I'd put more people in jail, but I'm not going to do it in violation of the Constitution."

After Scalia concluded his lecture, Scalia accepted several questions from the audience.

One student asked how Scalia interpreted questions dealing with technologies that did not exist at the time of when the Constitution was first drafted. Using the death penalty as an example, Scalia explained that if the founding fathers saw hanging as constitutional, then improvements in technology such as the electric chair must also be constitutional.

Another student asked about the right of the Transportation Security Administration to search airplane passengers. Scalia responded by defending the searches.

"I think it is within the realm of reason, if the threat is blowing up the plane," he said. "Would you rather be searched or blown up?"

A question regarding whether Scalia's originalism gave him a strict constructionist view of the Constitution drew a confident response from Scalia.

"I am not a strict constructionist," he said.

Scalia noted that it was vital to interpret the Constitution reasonably. As an example, he explained that he interpreted the First Amendment to allow free speech in the form of written letters, although the Constitution did not explicitly mention this.